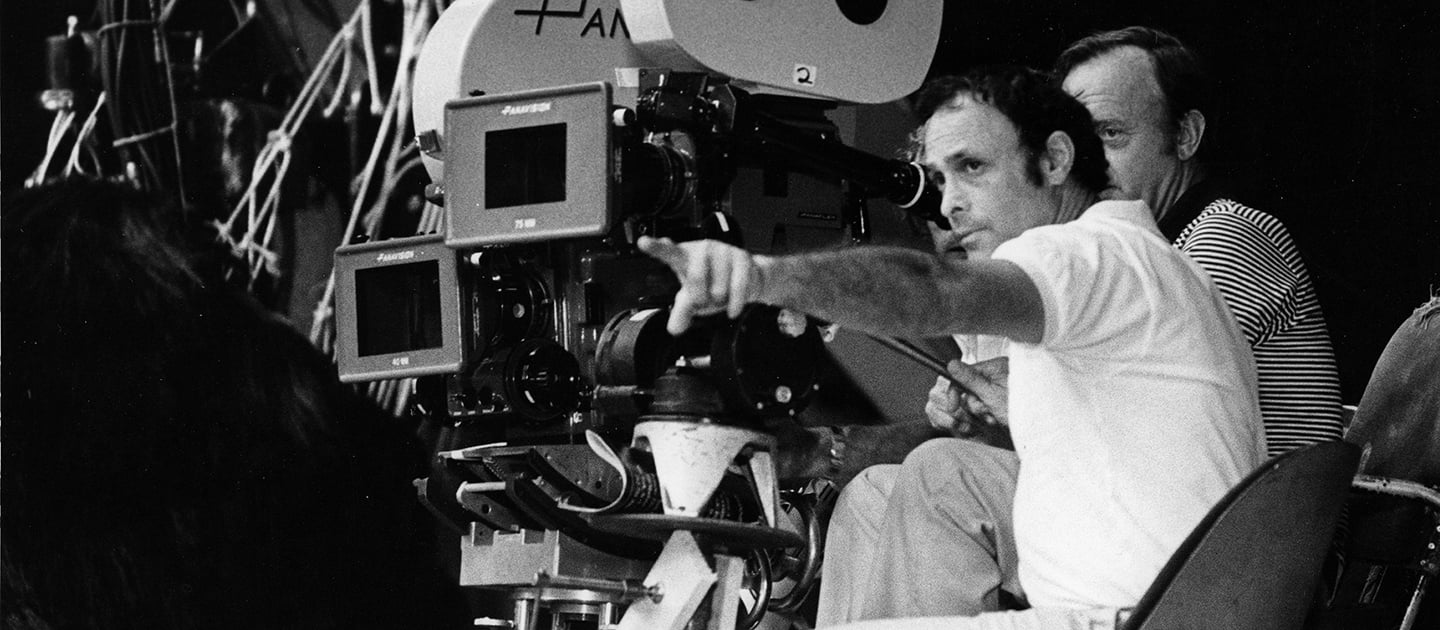

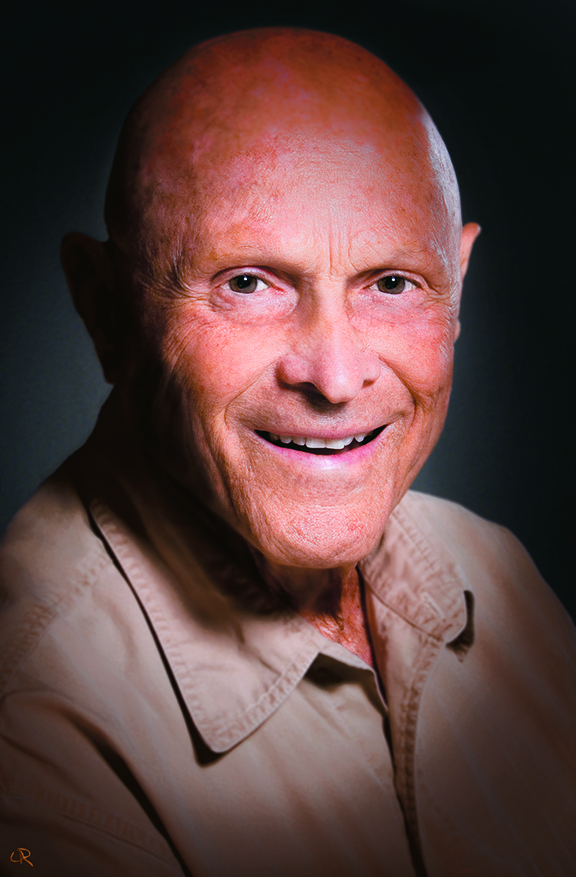

In Memoriam: Richard H. Kline, ASC (1926-2018)

An Academy Award nominee and recipient of ASC Lifetime Achievement Award, the esteemed cinematographer died on August 7 at age of 91.

Working for more than 40 years as a cinematographer, Richard H. Kline, ASC shot films of nearly every genre, as well as several that defied easy classification. Among his credits were Hang ’Em High, The Boston Strangler, Body Heat, Soylent Green, All of Me, Breathless, The Andromeda Strain, The Fury, Mandingo, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Howard the Duck and My Stepmother Is An Alien. He also shot several television pilots, including The Monkees.

With some understatement, he told American Cinematographer, “I tried never to repeat myself.”

Kline was born on Nov. 15, 1926, into a Los Angeles family that included three ASC cinematographers: his father, Benjamin H. Kline, and two uncles, Sol Halperin and Philip Rosen. However, he said, he took up camerawork at age 16 not out of any great love for the craft — his passion was surfing — but because World War II was raging, and his father believed such training would help him qualify for a camera unit when he was called to serve. He started at Columbia Pictures in 1943 as a slate boy on the Technicolor musical Cover Girl, and by the time he entered the U.S. Navy the following year, he had advanced to first assistant cameraman.

Kline was stationed at the Photo Science Laboratory in Washington, D.C., before shipping out to the Pacific theater. Following the war, he spent three years studying fine arts and art history at the Sorbonne through the G.I Bill. In 1951, he returned to L.A. and resumed working his way up the ranks at Columbia.

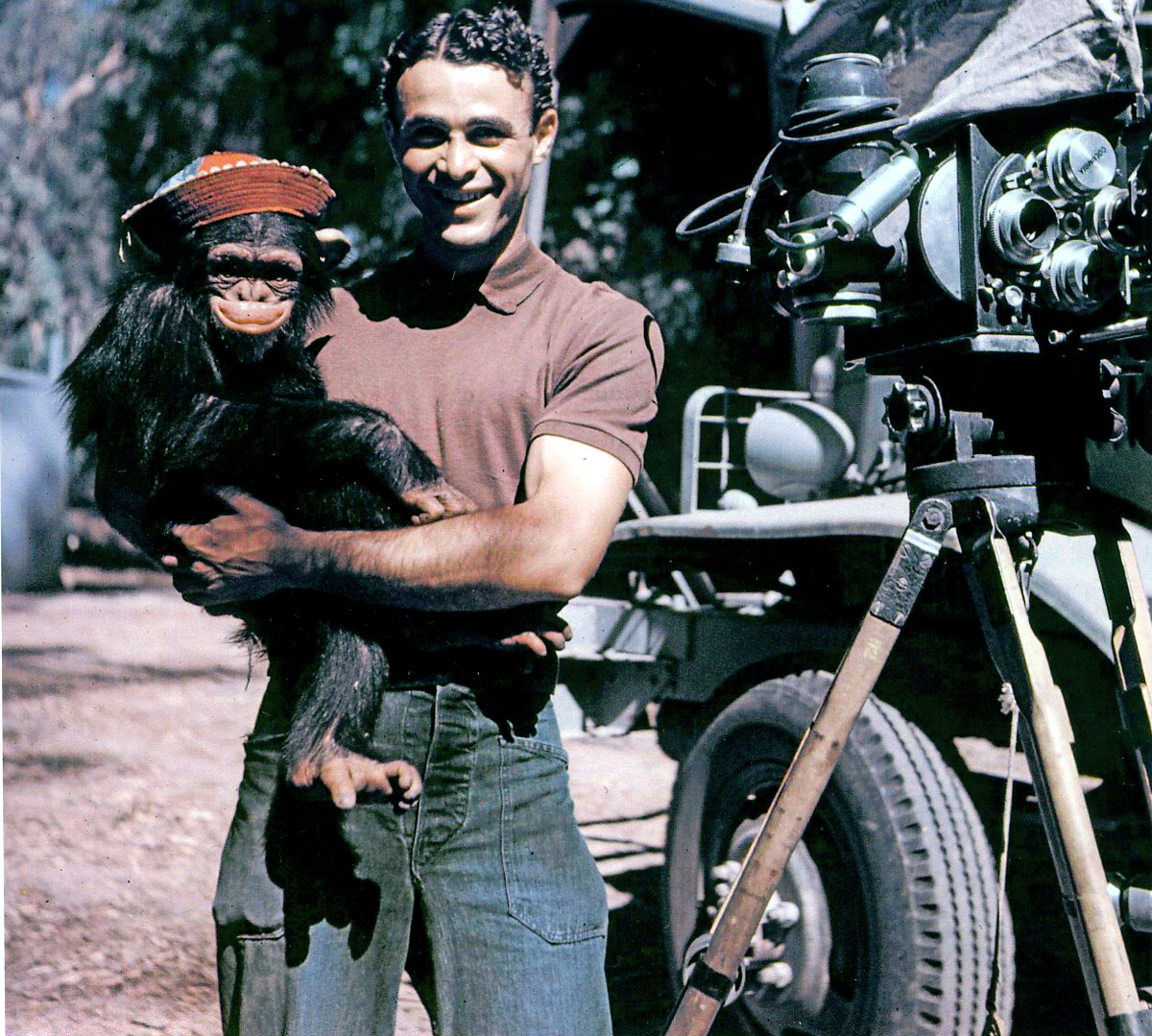

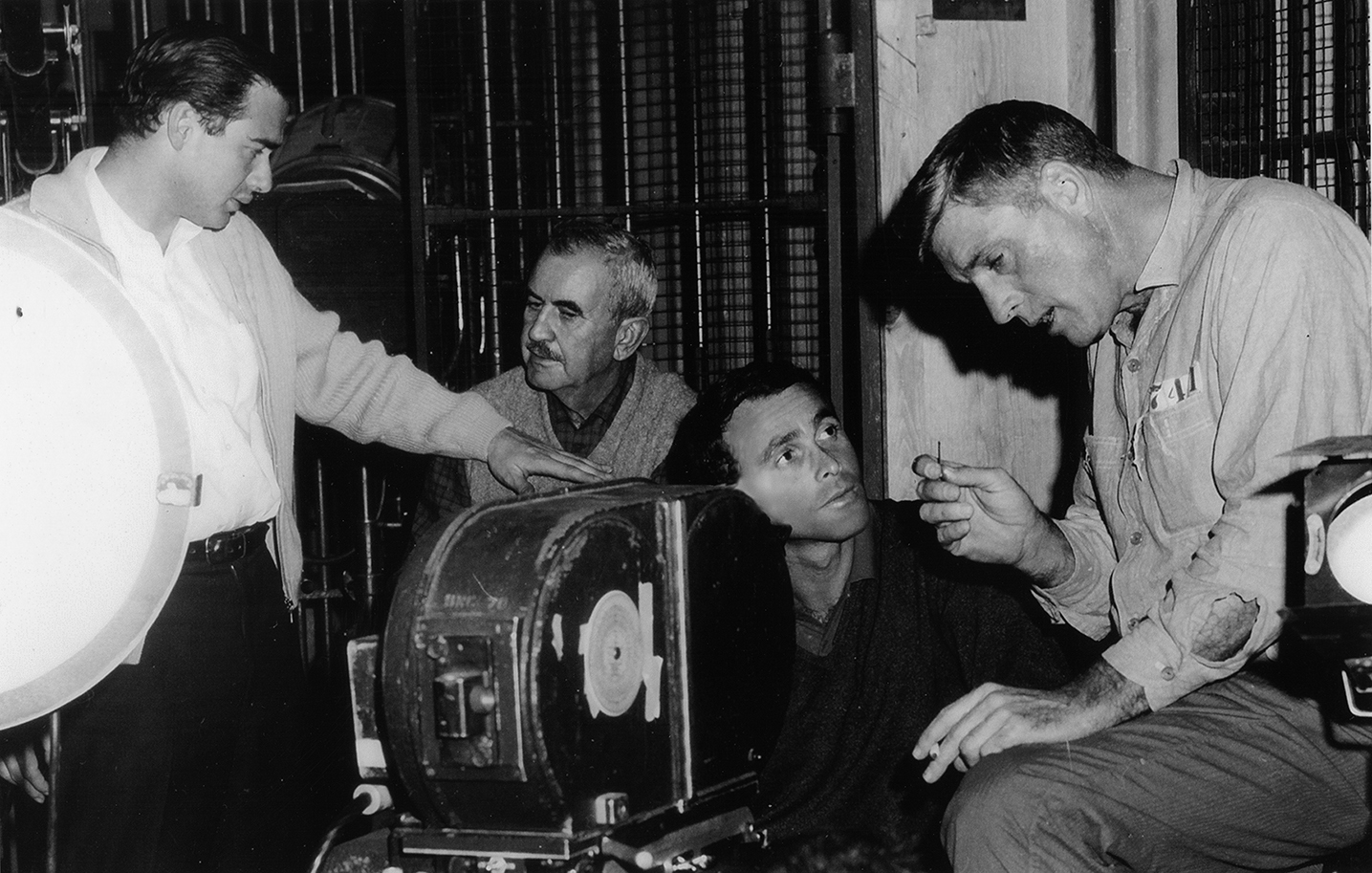

Kline assisted and operated on more than 200 motion pictures, working for such ASC greats as Charles Lawton Jr., Burnett Guffey, James Wong Howe and Philip Lathrop. He described all of them as mentors, but said he learned the most working as an operator for B-movie producer Sam Katzman. “We did 106 features in six years, B pictures like Rock Around the Clock, and I really learned my trade from that experience,” said Kline. Between features, he often worked on The Three Stooges short films.

Kline moved up to cinematographer on television’s Mr. Novak. At 35, he was “considered very young for the job … the average age of ‘first cameramen’ in those days was about 60,” he recalled. “I was at MGM when it happened, and the cameramen’s table in the commissary was a very closed group. I was almost embarrassed to sit there because I really wasn’t old enough!”

After shooting a few television projects, Kline landed his first feature, Joshua Logan’s Camelot. The film’s forest set filled every inch of Stage 8 at Warner Bros.-Seven Arts, and because he lacked the space to lay dolly track, he decided to embrace the zoom lens as “an adjustment lens,” changing the focal length incrementally to create the feel of moving shots; he liked the results so much that he used this technique throughout the shoot.

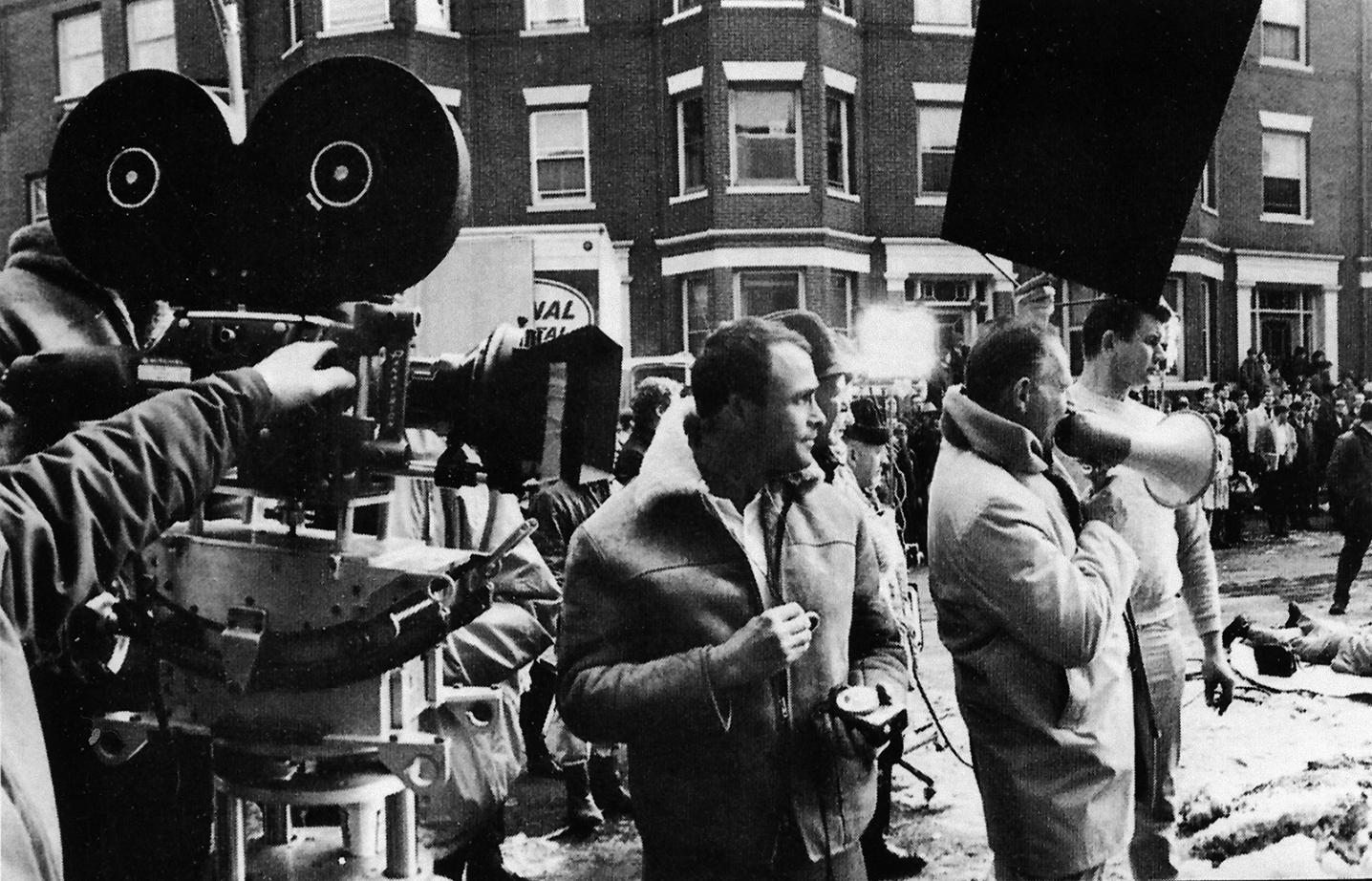

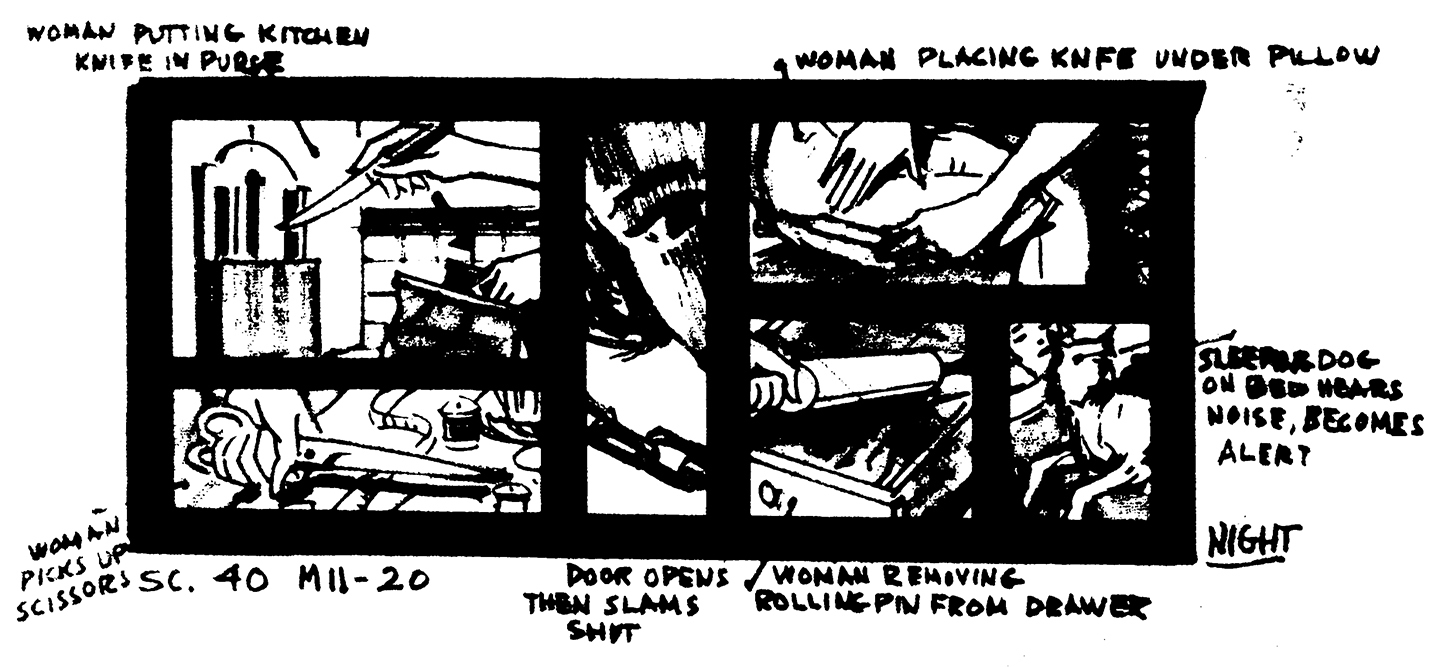

Zoom lenses also proved key on his next project, Richard Fleischer’s The Boston Strangler, starring Tony Curtis and Henry Fonda, which marked the first use of extensive split-screen photography in a Hollywood feature. Fleischer and Kline worked closely with visual designer Fred Harpman and editor Marion Rothman to plot the extraordinary number of separate setups required to create the multiple-image panels:

“Dick Kline understood so well what we were after, and he was extraordinarily good at getting it onto film,” Fleischer told AC. “Because he is so imaginative, he was exactly the right man to photograph this picture — ‘perfect casting,’ I would say.” Fleischer went on to collaborate with Kline on the features Soylent Green, The Don Is Dead, Mr. Majestyk and Mandingo.

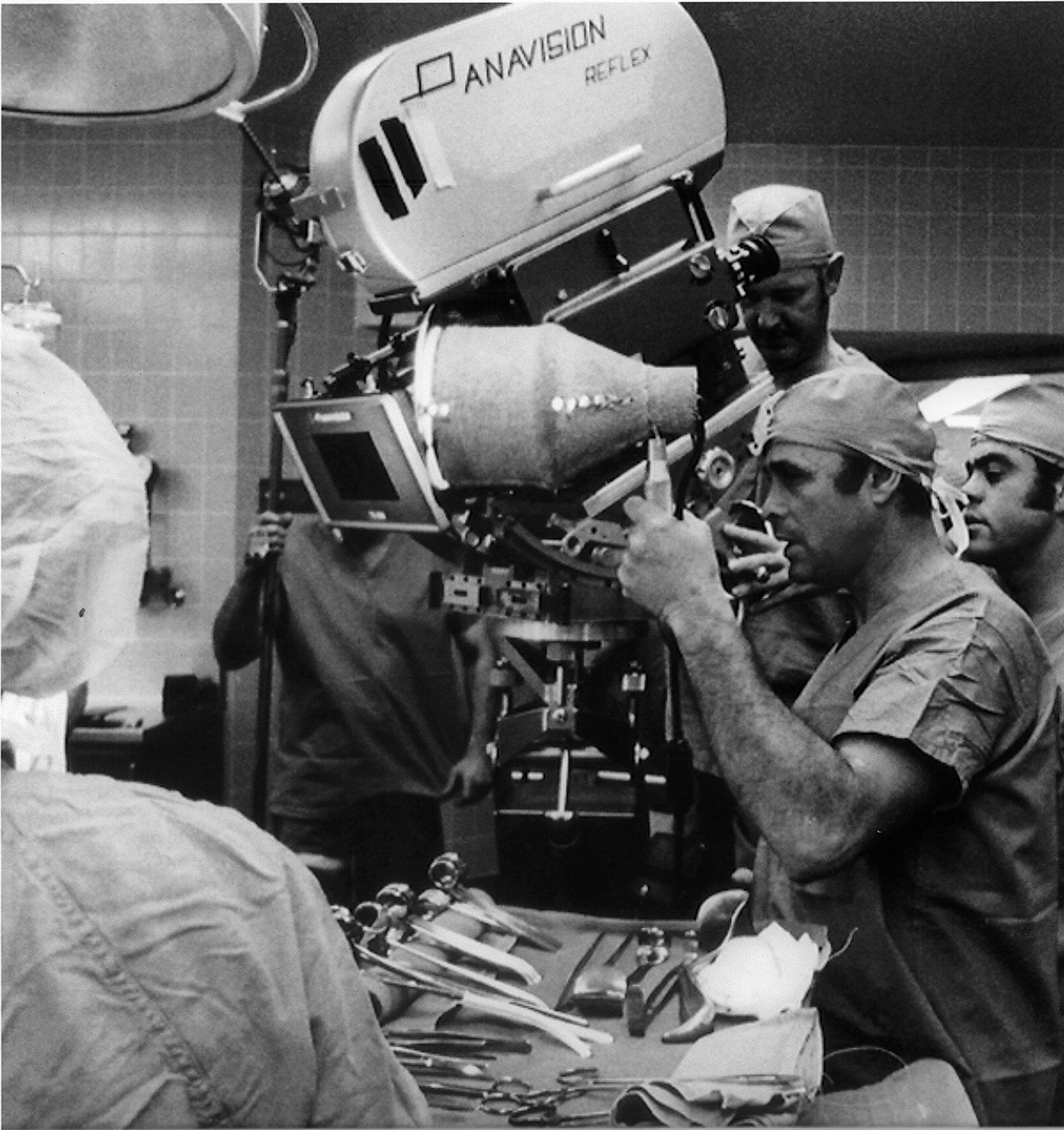

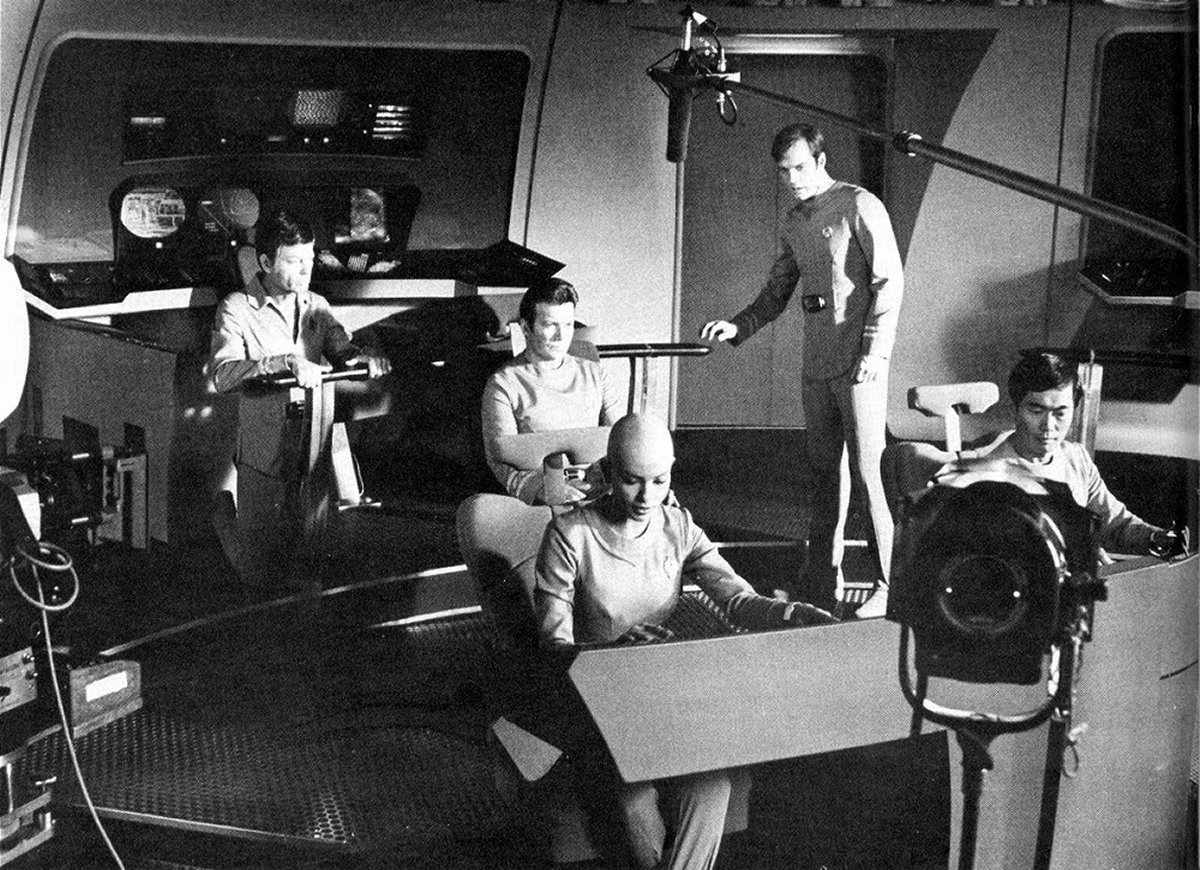

Kline also enjoyed working with director Robert Wise, whom he praised as “the most thorough and complete director I’ve ever worked with.” They teamed on The Andromeda Strain, where the goal was a thriller with a documentary look,and Star Trek: The Motion Picture, where they strove “to shoot the most sophisticated of all science-fiction films without sufficient pre-planning,” Kline told AC wryly.

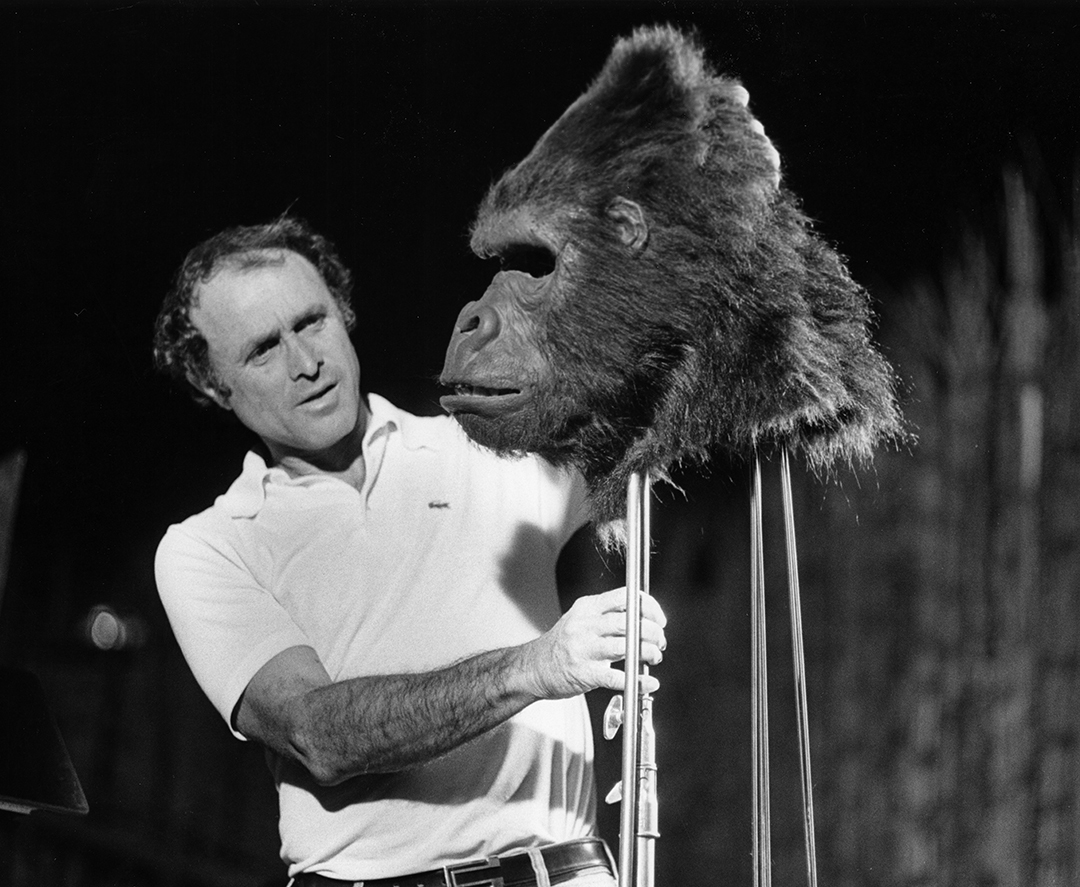

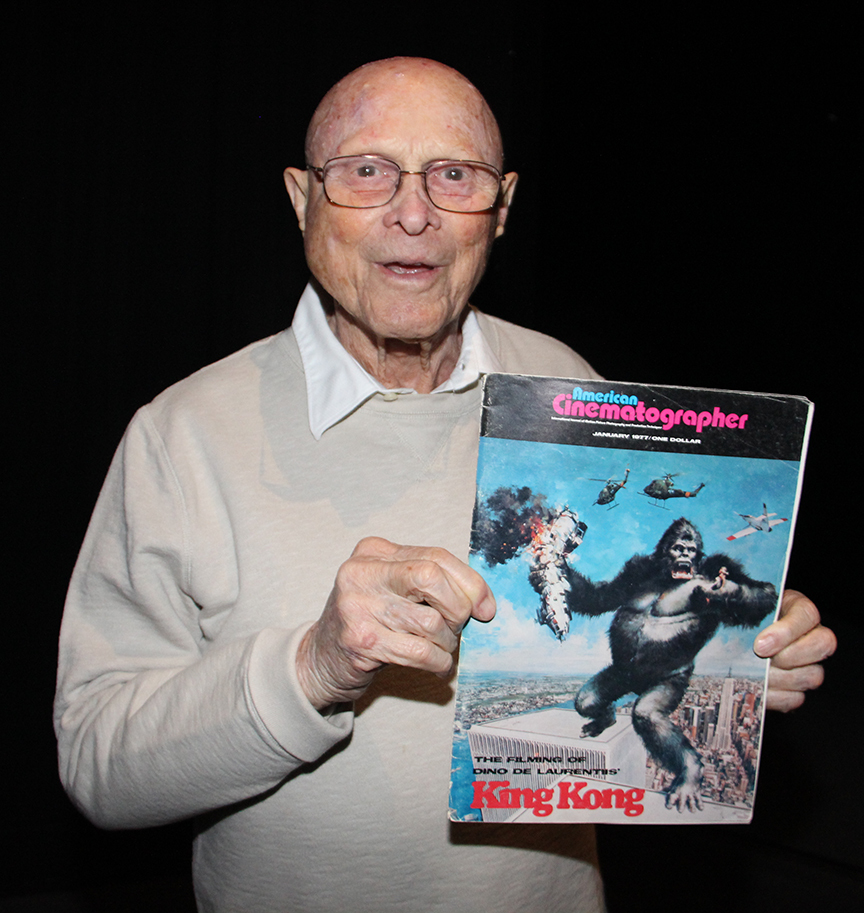

Kline received his second Oscar nomination for producer Dino De Laurentiis’ King Kong, directed by John Guillermin. “It seemed that each scene involved some unique element that required the ultimate in patience,” Kline wrote in his first-person account of the shoot (AC Jan. ’77).

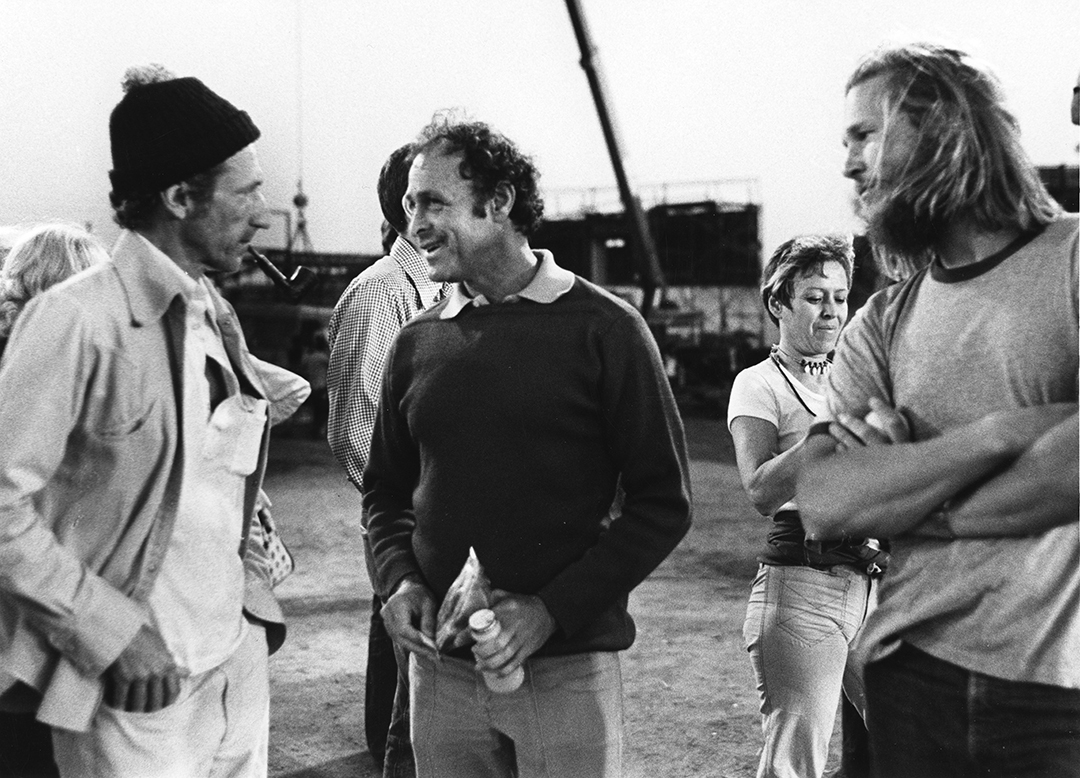

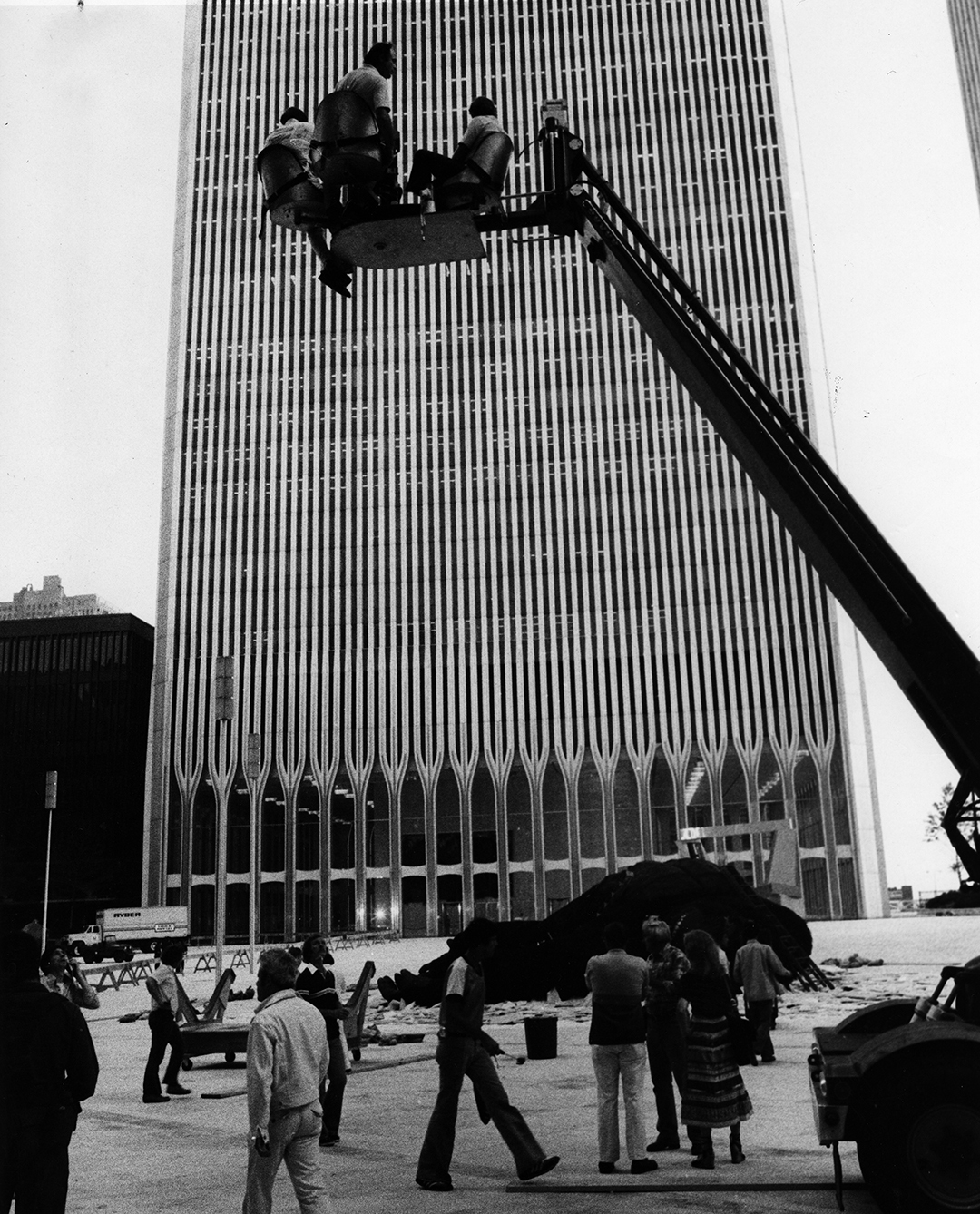

The many challenges included matching shots of a 42'-tall animatronic Kong with closer shots of a “miniature” (life-size) Kong portrayed by makeup-effects artist Rick Baker in an ape suit; filming some of the finale on location atop the World Trade Center; and achieving the proper light and exposure balance between the dark ape and his blonde co-stars, Jessica Lange and Jeff Bridges. “Reading a meter was impossible,” Kline wrote. “It was just a question of visual judgment, sighting it through the camera, and using rim lighting to make Kong stand out.”

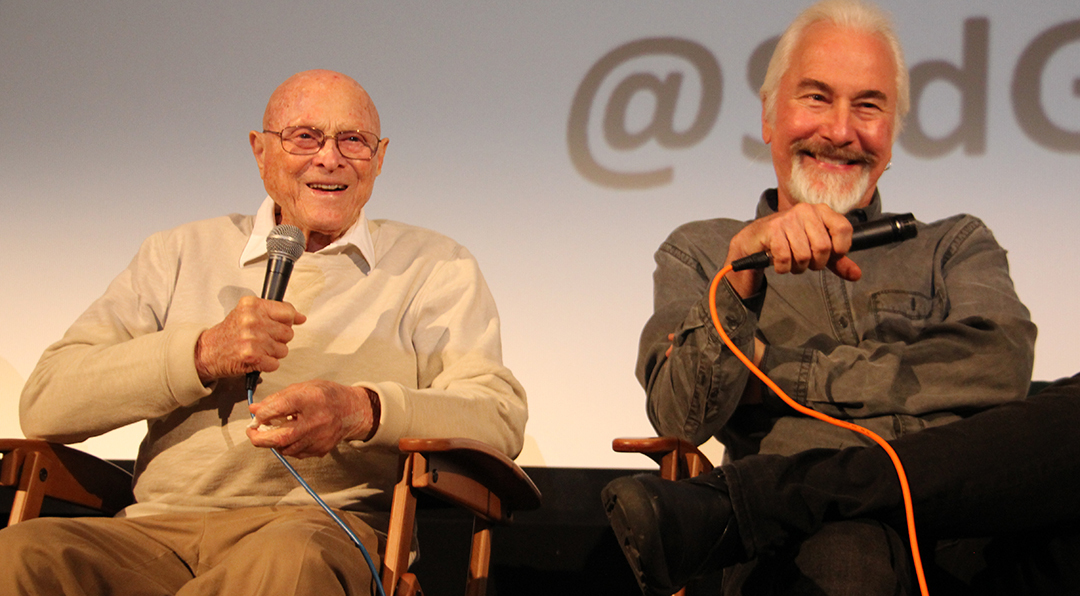

In December of 2016, the cinematographer participated in a special 40th anniversary screening of Kong at the American Cinematheque, where he was joined by Rick Baker and others for a Q&A session. (Brief story here, entire discussion here.)

Kline became an ASC member on Aug. 7, 1967, after being proposed for membership by his uncle, Sol Halperin. When he was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award 38 years later, he told Variety, “I’m the fourth member of my family to be a member of the ASC, and nobody else can make that statement. It’s very special.”

Kline is survived by family including his son Paul, daughter Rija and four grandchildren.

You’ll find an extensive profile on Kline here.