Bram Stoker’s Dracula: A Happening Vampire

Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK details his visual approach to Francis Ford Coppola's horror opus.

This article was originally published in AC Nov. 1992. Some images are additional or alternate.

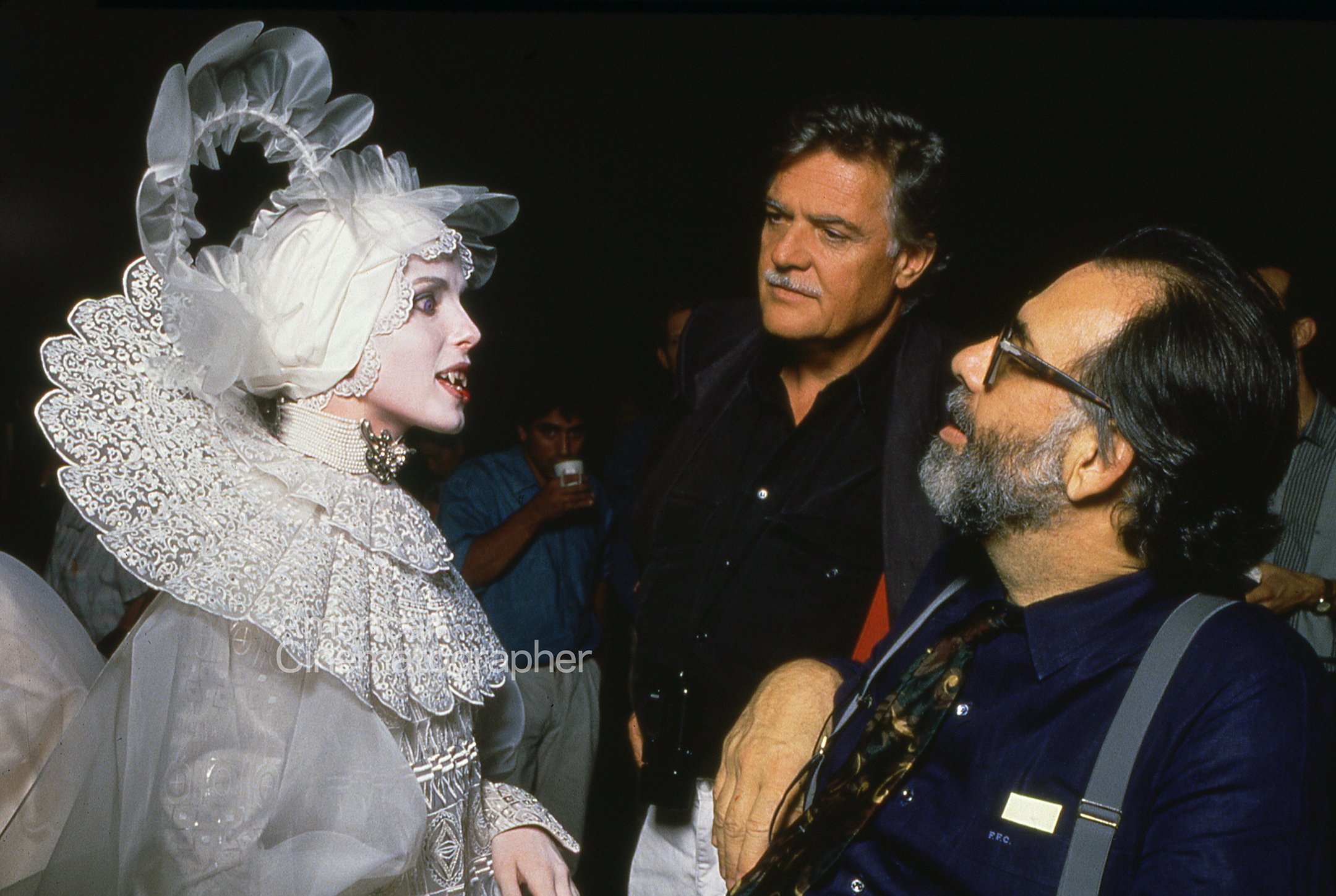

Unit photography by Ralph Nelson, SMPSP

In the main hall of an ancient, crumbling castle held together by massive pillars of rusty iron, a group of blindfolded men and women is herded together by a bearded man. They stand nervously as the man signals to an appalling monster, which appears to be half man and half wolf. The creature approaches each of the individuals in turn, nuzzling its hairy, misshapen face against theirs, running claw-like hands over their bodies as it snarls obscenities and makes perverted threats. The victims shudder and gasp.

This bizarre sequence of events took place last January on Sony Studios' Stage 30 in Culver City. The blindfolded unfortunates were actors appearing in Bram Stoker's Dracula. The bearded man was producer-director Francis Ford Coppola, and the monster was actually British actor Gary Oldman, transformed into the Count's wolf state by masterful makeup artist Greg Cannom.

"I use improvisations like this to almost program the actors," Coppola explained later. "I had them blindfolded with this horrible creature so that when they do meet Dracula they react. It prepares the actors, so that when we do the script they will be more like real people because of the instincts that have been put into them." The strategy may be unorthodox, but it makes sense. As Coppola noted, "The vampire myth speaks to the latent fears and desires in all of us."

“Something unusual about this movie is that we had 10 weeks pf pre-production. We met every day to talk over the scenes, and Francis told us what he wanted.”

— Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK

Coppola recalled that he had long dreamed of doing Dracula — not as it has been presented on stage and screen, but as it was envisioned in 1897 by the source novel's author, Bram Stoker. "In 1958, when I was a camp counselor — teaching drama, baseball and so on — I used to read to the kids at night. And the book I read was Dracula. By reading the book in its original form, I felt I knew something other people didn't know. The original was more of a Victorian adventure novel — almost like a Western, with pursuit on horses and fights. One of the heroes was a big cowboy from Texas! The movie that was most similar was Nosferatu, made in Germany in about 1922, but even that film was not very similar because [the producers] didn't get the rights to the book and had to make changes

"The greatest challenge was that I wanted to do something fresh, and there have been a lot of good Draculas; John Carradine was one of my personal favorites in House of Dracula. It's hard to work with a big crew of artists and technicians and tell them, 'I know that's the way to do it, but let's take a chance.' To do this story differently was the hardest job I ever tried to do. I wanted this to be the one most like the book, and it is — all except the prologue, which starts in the early part of Dracula's life."

For Coppola, fidelity to the book meant more than just sticking to the original story. "The period of the book was the dawn of new technology," he explained. "I wanted to make the picture almost in the style of the turn of the century, when motion pictures were the domain of the magician. It would be interesting, I felt, to make it as if we were filmmakers in those days, with all of the naive effects of that time. Underneath, it's a movie about passion, and I thought it would have more 'soul' if there were less technology. We actually used an old Pathé camera once! Of course, it wasn't possible to do all of it in the old way, so we did do some postproduction effects."

The casting has aroused some controversy among those accustomed to a Count Dracula played by continental smoothies like Bela Lugosi and Louis Jourdan or seasoned character players like Carradine and Christopher Lee. Coppola's choice of accomplished young English actor Gary Oldman certainly represents a new image for Dracula, and others in the cast also herald a break with tradition. That popular portrayer of teenagers, Wynona Ryder, is a far cry from the swooning ladies who have portrayed Miss Mina, while Dracula's nemesis, Van Helsing, is essayed not by an elder statesman but by the brilliant but comparatively youthful Anthony Hopkins. "I wanted a young cast," Coppola said. "What I liked about Oldman was his passion; the story is ultimately about love."

Coppola's unabashed appreciation of cartoon art led to another interesting personnel decision. "I learned to read from comic books," he noted. "I could read when I was five, before I went to school. That's why I asked [noted cartoonist, illustrator and editor] Jim Steranko to help me in the early phases of this picture."

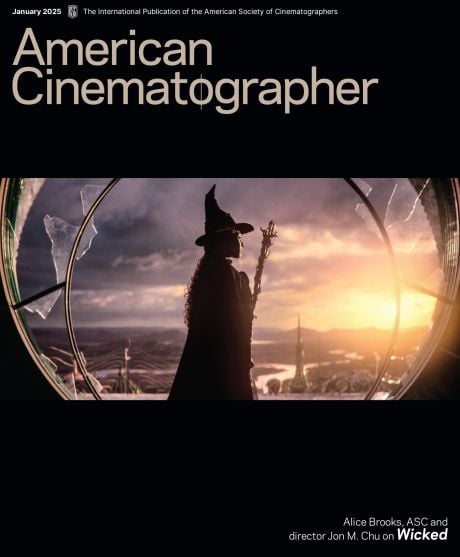

Back on Stage 30, we watched director of photography Michael Ballhaus, ASC, BVK photograph a highly imaginative sequence: Dracula and Mina are waltzing to a lush classical score amid a sea of tall, white, flame-tipped candles against a black void. The Transylvanian nobleman is slender and young-looking, with a backswept mane of long black hair. The dark-haired, dark-eyed woman, young and beautiful, appears entranced. Her partner seems in the grip of an obsessive intentness, yet their movements are graceful and swift — alarmingly so. They swirl so dizzily that the wax pillars appear to be spinning counter to their movements.

Suddenly, an eerie vision fades into view in the blackness beyond the couple: a tattered and terrified man is pursued down a castle stairway and across a flagstoned courtyard by three gorgeous women wearing flowing white shrouds and expressions of wolfish hunger. The fleeing man brandishes a large metal cross as the hellish women try to overwhelm him. Snarling, they cringe back, then lunge after him again. The vision fades to black again as the music plays on, and the dancers continue their frenzied waltzing until the 120 candles are extinguished.

The scene was repeated many times before Coppola finally called "Print!"

On film the scene proves even more striking because Ballhaus photographed the action from a circular track; his camera moves past the candles so that they seem to be spinning around the dancing couple. The German-bom cinematographer has used circular dolly tracks often since 1973, when he introduced the idea in Rainer Wemer Fassbinder's Martha.

Some weeks after the shoot, Ballhaus reported that the scene's "background vision" was not retained in the final cut. "The candle scene survived, but the transition from the dancers to the other set didn't make it. It was exciting to do this kind of transition, but sometimes [such techniques] are confusing to the audience. The viewers think they are in the ballroom and all of a sudden they see the courtyard of Dracula's castle, which throws them off a little. I think that's why Francis took it out."

The "vision" was done in the camera rather than as an optical effect. The ballroom was actually set up in the courtyard of the castle, while the chase was staged in the background and lighted separately. Ballhaus noted, "We shot almost every scene on the stage, except for one scene that was made on Universal Studio's New York Street, which we redressed as a London street. It was a magic hour shot done in daylight.

"Something unusual about this movie is that we had 10 weeks pf pre-production. We met every day to talk over the scenes, and Francis told us what he wanted. Then I tried to make a shot list and bring it into a certain order. Then we talked about the shot list and gave it to the production illustrators, who created the storyboards according to the information we gave them. [If it] wasn't quite right, we changed it. By the time we started the movie every shot was a drawing — [the entire film] was laid out like a book. Francis said, 'This is what we want to do; this is our Bible.'

"We stuck to it pretty closely, but after about ten weeks he may have gotten a little bored with it," Ballhaus chuckled. "He said, 'Okay, now we want to do something totally different.' But we went back to it pretty fast and stuck to the content of what we had worked out together up front, and that helped us to move faster. Francis inspired us to do things by just talking about his incredible fan¬ tasies and what he would like to do. We couldn't fulfill all of his dreams and fantasies, but a lot of what he really wanted to do is in the picture."

There is no "formula" lighting in Dracula. "Because there were no electric lights in Dracula's time, all the light sources were either fire or oil lamps or torches, and all of these sources are unsteady — the light is constantly moving," said Ballhaus. "Most of the time we had the lights on flicker boxes to give them a slight motion, which works out well for me because I like any kind of motion. Since we had a legitimate right to have the lights moving we did so in almost every scene. "

"Also, I worked a lot more with direct light than I normally do. Usually I bounce a lot and work with soft lights. Here I used a lot of direct light to create shadows, to create darkness; it's almost a "black -and-white" look and I like it. We also had a chance to work with low lights. In one scene, a fireplace was the only light in the room, so we used three 5Ks with different gels. We used a lot of half-sepia, full-sepia and amber in a mixture of warm lights, with all three on flicker boxes working against each other so they never repeat the pattern of the light source or the flicker."

Ballhaus pointed out that the on-screen light sources provided other weird atmospheric touches, such as smoke emanating from torches. "We always had some smoke in the air in Transylvania," he recalled. "For scenes in England, we had a lot of smoke and fog. We had excellent special effects people who helped us do all these things, like smoking up the huge stage in almost no time. We had snow storms with big ritters [wind machines] blowing snow into the air and a lot of other big fans on cherry pickers high up.

"Gary Oldman is quite a change of pace from all the other Draculas," Ballhaus confirmed. "It was quite tough for him because he had a lot of different makeups. When he was the old man in his castle we tried to make him look eerie. First you see a huge shadow on the wall, then we pan over and there is the old man with a lantern in his hand. It was a Turkish lantern with little patterns that created weird shadows as the light moved and turned on his face. There was a small quartz bulb inside the lantern, battery-powered from a cable running up his arm. That was the only light on him; everything else was lighted separately. [Then] he goes up the stairs, and all of a sudden he disappears!"

In the same scene, back projection was utilized in a curious way for surreal effect. "We shot one part live and the other part was projected, so that Harker (Keanu Reeves) is walking in front of Dracula's back-projected image," Ballhaus said. "Then Dracula disappears, and in the next second he reappears behind Harker. It is surprising, unsettling. You never know where he is. First you see him with his shadow on the wall — at least it seems to be his shadow — but suddenly the shadow takes on a life of its own and starts trying to strangle Harker although Dracula is still standing there! It was quite complicated to do. We had a projector behind [Gary Oldman], and a dancer created his shadow and doubled his movements in sync with him. We had to rehearse it over and over again to make sure that he was absolutely in sync, but it worked out quite well.

"The scene in which Dracula and Harker walkalong the hallway was lit by big oil lamps and torches. For some scenes that light gave us a good reading, but we filled in with softer units on a flicker box or in chicken coops so the actors go through light areas and dark areas. Darkness is an important part of this movie."

The cinematographer soon came to share Coppola's fascination with early cinematographic techniques. "They did some pretty amazing effects in the old days," he said. "You look at a movie like Nosferatu and they have things in there that are quite thrilling. They didn't have ILM to do their tricks for them, so they had to do it in the camera."

For Ballhaus and Coppola, the in-camera, classic approach to special effects was facilitated by a sophisticated, high-technology tool — the Arriflex 535 camera. "Using the new Arriflex 535, we tried to do a lot of things using the old way, such as double exposure when somebody appears and disappears," the cinematographer says. "We did all the speed changes so that Dracula sometimes moves swiftly in an unreal way from one room to another; it seems as though he's flying through the room rather than walking. Let's say he's 15 feet away from Harker and suddenly he's right next to him. It happens in a second because we changed the speed from 24 fps down to 8 fps. Gary Oldman would race into the frame, and then we would go back to 24. We also had Dracula on a little dolly and moved him fast toward Harker. I've never done anything like that before! The camera takes care of the exposure with the variable shutter. It was a tricky thing to do back in the old days, but now it's nothing! You tell the computer in what time period you want to change, then you push the button and it does it all by itself. And if you go from five fps to 50 fps exposure it is absolutely 100 percent correct.

"This new camera can do many things," Ballhaus enthused. "We did a lot of action backward. We were rolling the cameras backward and the actors were playing backward — for instance, when Lucy becomes a vampire she comes down to a crypt carrying a child in her arms which she's about to bite to suck the blood, but [Van Helsing and his men] are waiting for her. We had her walk up the stairs backward and the cameras went on when she entered the crypt. It looks almost real, but there's a strangeness about it that makes it magical. And the moment when she slips into her coffin was also done in backward action. It looks great because the fabric moves differently; you can't tell what's wrong, but something is weird and it makes all the difference. These are subtle little things that we didn't do in the usual way of simply giving it to one of the wonderful postproduction companies. We tried to do it in the camera on the set, and that made it exciting because we were part of the process when it was happening. It wasn't taken out of our hands."

Ballhaus noted that in Nosferatu some scenes were cranked erratically to give them a jerky, stop-motion look. "We did that too — we call it pixilation. We'd do frame-by-frame exposures, then move the camera and do a couple of frames, and so on. We did it sometimes for Dracula's point of view or the wolf's point of view; it gives a strange and different look. For the first scene when Dracula comes to London, it is his POV. He has come from Transylvania where he only had a couple of Gypsies around him, and now suddenly he's in the midst of all this life in the streets of London. We wanted something special, and Francis has an old Pathé camera that is still intact and works quite well."

The camera is the same model that Billy Bitzer used to photograph the early films of D. W. Griffith, with square magazines, an upside-down viewfinder, a handcrank on the back and a tiny f4.5 lens.

"We actually did Dracula's POV with Francis' Pathé, hand-cranking on a crane. You can't believe how good the quality of the lens is!" Ballhaus exclaimed. "We loaded it with 45 and cranked at about 18 fps. It gave [the footage] a strange, period look — you think you're right there at the first movie theater in London. Every time you do something new it's a little tricky because you don't know how it will turn out, but I got a lot of kicks out of that one!"

In the film's climactic chase sequence, Dracula is pursued as he attempts to get into his castle before the sun sets and he regains his full powers. The sequence was shot entirely on Sony's Stage 15. Ballhaus said he was worried at first about the interior staging. "When they said they wanted to shoot all this on stage I was a little scared, because I've shot on a stage a lot, but never a race like this! We had 15 horses on that stage. I was afraid it would be too repetitious when they were going around and around, and finally you see the same tree again and again. But it wasn't true — you can never see that it was on a stage. The light is beautiful, it's all foggy, and it worked quite wonderfully.

The difficult part was that the horses were going in a circle but it had to look as if they were constantly racing away from the sunset, with the sunlight on their backs. We had to have three different suns so that they'd go from one and then to the other but with the same backlight situation. For this huge stage, which is 300 feet long and 150 feet wide, we had a special light called Ray Beams. It consists of 30 1,000-watt quartz bulbs mounted in one maxi-group; it's extremely strong. We had four of them in different positions and spaced so that when the riders were in front of them they were always backlit; as they ran out of one they came into another. We put a gel in front, half-orange to simulate a warm late-in-the-day sunlight, and the whole stage was covered with chicken coops which were half-blue, so that we had a color difference between the warm sunlight and the blue of last daylight. There are eight 1,000-watt bulbs in each coop — that's a lot of amps. It made a wonderful mixture much like the 'magic hour.' There was snow blowing and a lot of fog to get the eerie look of the Transylvanian mountains. The whole thing was quite tricky."

A second camera was utilized in some of the chase scenes, but only sparingly elsewhere. "It's not easy to light a scene for two cameras, and sometimes you spend more time trying to figure out how to do it with two cameras than it's worth," Ballhaus said. "But there are times when you need them."

Another challenging sequence in Dracula depicts Mina, still under the Count's love spell, aboard a ship to Transylvania, where she is to marry Harker. As the ship sails on, she destroys her diary, casting the pages into the sea. "We didn't have a real set for it," Ballhaus revealed. "There were a couple of ropes, a railing, and some elements of a ship. We just moved the whole thing, had smoke and blowing winds, lit it as though everything was in motion, and it was a wonderful illusion. It looked as if you could feel the breeze off the ocean and see the ship's lights dangling. I like this kind of thing, creating an illusion with almost nothing. Sometimes it is better than reality."

All "daylight" scenes were played on the stages. The Esther Williams swimming pool on Stage 30 (Sony Studio was in MGM's domain in the 1940s when the "Million Dollar Mermaid" created her aquatic ballet sequences) was transformed into a sunken garden at Mina's home.

"We had scenes there that began in bright daylight, then suddenly changed to rain and clouds," Ballhaus said. "We had a big rig so we could have plastic clouds on ropes moving in front of the chicken coops on top to create the shadows of clouds on the set. It's great to be able to create whatever kind of light you want. On one set we used 60 chicken coops. Underneath the coops, we had a big silk to make them seem to be only one light source, and also to create a kind of hazy London atmosphere. When you're on a real location you're always restricted in a way; either you're at the mercy of the weather or else you have no time to do it. You can't do one shot every evening and then come back. It's much more interesting to create your own world."

Several years ago Ballhaus told AC about his urge to operate the camera himself, as he had done in Europe. "My operator, David Dunlap, does such a great job that I don't feel the desire any more to do it," he confessed. "We've worked together for 10 years. My son, Florian, is my first assistant and the gaffer is Jim Tines, a creative artist with a lot of good ideas. Pat Daley is the key grip. They're fast, efficient and prepared, and they think ahead. These elements become more and more important because money is getting tight and you have to work fast and be efficient. We finished this picture on time."

Daley came up with a simple but ingenious solution for one important piece of action. The scene took place at the crossroads in the fictional Borgo Pass, a desolate setting of snow-covered rocks and dead trees. A Slovak coach arrives and drops off Harker, leaving him alone. Harker hears wolves howling; looking up, he spies a huge cross upon which hangs not Christ but a monstrous wolf man. Suddenly, the black coach from Castle Dracula arrives. The mysterious driver reaches down with what seems to be an arm 10 feet long and lifts Harker by the shoulder into the coach!

"Francis wanted something special there and we showed him an idea where we had Harker on a board and pushed him in," Ballhaus remembered. '"That's not weird enough,' he told us. 'I want this arm to really stretch out and get this guy.' So Pat came up with an idea and two hours later they were ready with a rig, which we showed to Francis. We had a wide shot and we tracked in and lost the body of the coachman. We had the seat of the driver on a slide, and we slid it over to meet Harker. Harker was on a see-saw. Somebody stood on the other end and elevated him, and Gary pulled him into the coach. Francis smiled and said, 'That's weird!' You have to know how to do it, but it's simple compared to the tricks in a movie like Terminator 2. [Those effects] don't give me a kick because I know it's all computerized.' This film gives you a kick because you really don't know how we can do a shot like that — it's closer to reality and that makes it more human and more personal. That's the difference that makes you care about it."

Ballhaus made extensive use of filters on the film. "Every shot was filtered," he revealed. "With the 96 film I used a 1.8 ProMist; otherwise it would have been a little contrasty. That contrast is nice some of the time, but most of the time when you photograph faces it's too contrasty. I used some black nets to soften the ladies. In trying for a period look I found that the lenses were too sharp, so I used the black net 2B and the ProMist. I used the double fog for some of the scenes where I really needed diffusion."

About three quarters of the movie takes place at night, lighted by fireplaces or torches or candles. "To get some contrast, I kept it a little cool when you see something outside, such as having a half CTO for inside and half blue for outside, so there is at least 1,000 degrees K difference," Ballhaus related. "In Dracula's castle, we gave the moonlight that comes through the roof a cold, bluish look. There are some shots in the castle with a lot of space where you get the feeling that it's quite huge, such as high-angle shots of people walking over a painting on the floor.

"Roman [Coppola] and Steve Yaconelli [ASC — second-unit director and cinematographer, respectively] did an excellent job of matching what we did. That is most important. It's a hard job to match what the first unit did. A lot of the special effects were second unit because we had no time to spend on them. They make the movie so rich and scary."

For the first time since he came to the U. S., Ballhaus used a small lab, FotoKem. "Mark van Flom did an excellent job," he reported. "It wasn't easy. I shot the whole picture on 96 because the 93 wasn't yet available when we started, so I overexposed it one stop and pulled it in the lab one stop so we'd lose grain. That worked really well. We had rich blacks and a wonderful negative."

After the shoot had wrapped and he had begun working weekdays on a new picture for director James Brooks, the notoriously tireless Ballhaus was spending his Saturdays at FotoKem overseeing the timing for Dracula. "You have to be there until the last moment," he maintained. "It's very important, especially on a movie like this one."

Michael Ballhaus passed away in 2017 at the age of 81. His son Florian is today a member of the ASC.