On the Fast Track for F1: The Movie

Claudio Miranda, ASC, ACC and director Joseph Kosinski tap customized camera solutions to put viewers in the driver’s seat.

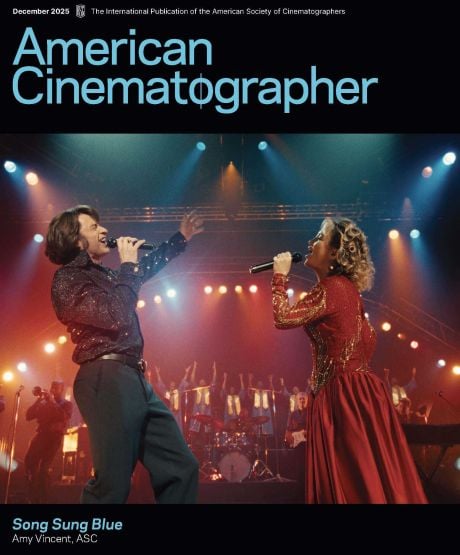

This in-depth look at the making of F1: The Movie first appeared in American Cinematographer's August 2025 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

The filmmaking team behind F1: The Movie wanted audiences to experience all the speed, g-force and high-risk danger of Formula One racing. To that end, cinematographer Claudio Miranda, ASC, ACC and director Joseph Kosinski collaborated with Sony on customized cameras small enough to be mounted on a racecar but with a sensor large enough to capture images that could be shown on both standard theatrical and Imax screens, per the studio’s distribution strategy.

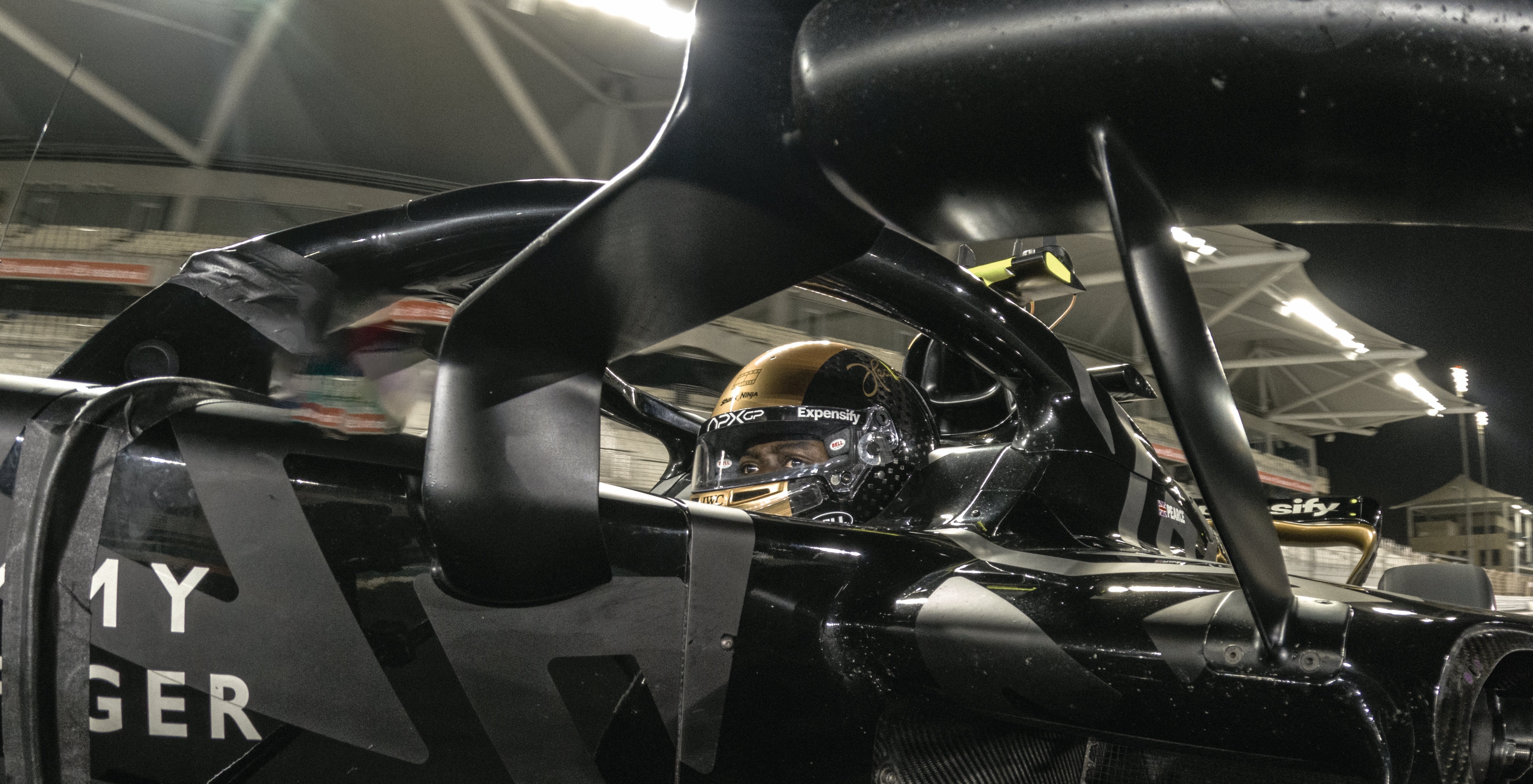

F1, Kosinski and Miranda’s sixth feature collaboration, finds former hotshot Formula One driver Sonny Hayes (Brad Pitt) playing out his career in whatever class he can get a ride. He gets another chance in the big league when former teammate Ruben Cervantes (Javier Bardem) persuades him to join his struggling APXGP (or “Apex”) Grand Prix team and mentor headstrong rookie driver Joshua Pearce (Damson Idris).

Kosinski and Miranda started discussing the project when they were shooting Top Gun: Maverick (AC June ’22). “While working on a movie together, we’re always talking about the next one and what we could do better,” the cinematographer says, joking, “That’s what keeps me around.”

For their F1 research, the pair screened various racing movies but thought few achieved the verisimilitude they sought. Miranda recalls: “What I didn’t like was that when the camera perspectives were outside the cars, it looked fast, but when they were inside them, it felt like a taxi ride.”

Getting the true feeling of speed became a major challenge for the filmmakers, since the average racing speed of an F1 car at 120 mph is difficult to fake, and the typical cheats and techniques just wouldn’t pass muster. Miranda continues, “It would be hard to fake the speed on a biscuit rig [either remote or with a pod driver] that can only go 60 mph on the straights and 20 mph around a corner. That would be sad.”

The notion of using a more standard remote-arm chase vehicle was also rejected, as it could never compete with the actual speeds of the F1 cars on the track.

“It was suggested that we should shoot on a volume stage,” Miranda adds, “but doing that or using bluescreen would also be sad — there would be no kinetic energy. Joe and I were not interested in that kind of approach.”

Another potential cheat strategy would be to speed up the image, which the filmmakers only wanted to do to a minor degree. “If you’re speeding things up from 20 mph to 200 mph, people start to look like weird bobbleheads,” Miranda explains.

Complicating things even further, Pitt and Idris would be doing most of their own driving. “Everyone was saying, ‘Do we really want an actor like Brad Pitt going 150 miles per hour?’ But as production went on, Brad became a better and faster driver.”

So, that became the accepted strategy: Let the actors drive for real and keep the camera footprint on the cars as low as possible. “Ideally, we wanted our drivers to match F1 speeds, but that’s impossible when the cars are carrying the kind of camera gear we added to them. So, we cheated [by speeding up some shots just] slightly.”

The mission, he asserts, was to be “as realistic and as fast as possible.” One particular film that did inspire the filmmakers was John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix (AC Jan. ’67; see Wrap Shot, page 72), shot by Lionel Lindon, ASC. The 1966 film features groundbreaking aerial work, as well as footage captured from onboard cameras that could rotate from the driver’s POV to a shot on the driver, proving that actors James Garner and Yves Montand were actually behind the wheel. “It was a big reference for us,” says Miranda. “There’s awesome stuff in that movie.

In those days, they didn’t have the visual effects we have now, but we wanted to stay away from digital enhancements as much as possible and capture as much as we could for real.”

“A Sensor on a Stick”

In configuring cameras to capture race footage, Miranda says, “I tried putting every camera body in front of the drivers, but they couldn’t drive with even the smallest ones in front of them — even the Sony FX3 was too big. And, for our purposes, small prosumer action cameras were crappy.”

The filmmakers initially considered using the “Rialto Mini,” Sony’s new, smaller Venice extension system, but Dan Ming, Miranda’s longtime 1st AC, explains, “We decided it was still too large.”

The result was a new prototype camera made by Sony specifically for the production. “I told Sony I wanted a sensor on a stick,” Miranda says. Ming adds, “Sony offered to take the recorder base from the more compact Sony FR7 PTZ robotic camera and design smaller-head units to house the 4K full-frame sensor,” explains Ming.

The camera the filmmakers created with Sony was officially called “the Prototype,” but nicknamed the “Carmen” — a reference to Brazilian singer and dancer Carmen Miranda, who shares the cinematographer’s surname.

The Carmen was a stripped-down, modified Sony FX6. Miranda had the auto ND-filter mechanism removed, keeping only the ND slide, which would go behind the lens. He notes, “That was critical, because one of our favorite lenses is the 10mm Voigtländer, and it’s impossible to put an ND in front of it. We used the Carmens a lot in the cars, and they just got hit and pelted with debris. We went through a lot of them.”

Voigtländer Hyper Wide Heliar rectilinear aspherical 10, 12 and 15mm lenses captured the actors’ performances in the cars with good geometric-distortion correction. For tighter angles or looking out at the track, says Ming, they used Zeiss Loxia E-mount lenses, which they had tested extensively on Top Gun: Maverick.

Ming adds, “We used standard FX6s as crash cams on the ground, and on cars that were to be crashed. Another cool piece of kit we had was a fully remote-controlled, full-size car that could be driven from a simulator setup. This allowed us to drive the car into the wall and stage other dangerous setups without risk to the drivers. Those cameras were streaming live video links for the drivers to drive with, and we had rigged FX6s in crash boxes for the impacts.”

Gearing Up

The filmmakers had the full cooperation of Formula One, and seven-time F1 champion Lewis Hamilton signed on as a producer, facilitating introductions to other league figures and serving as a technical adviser.

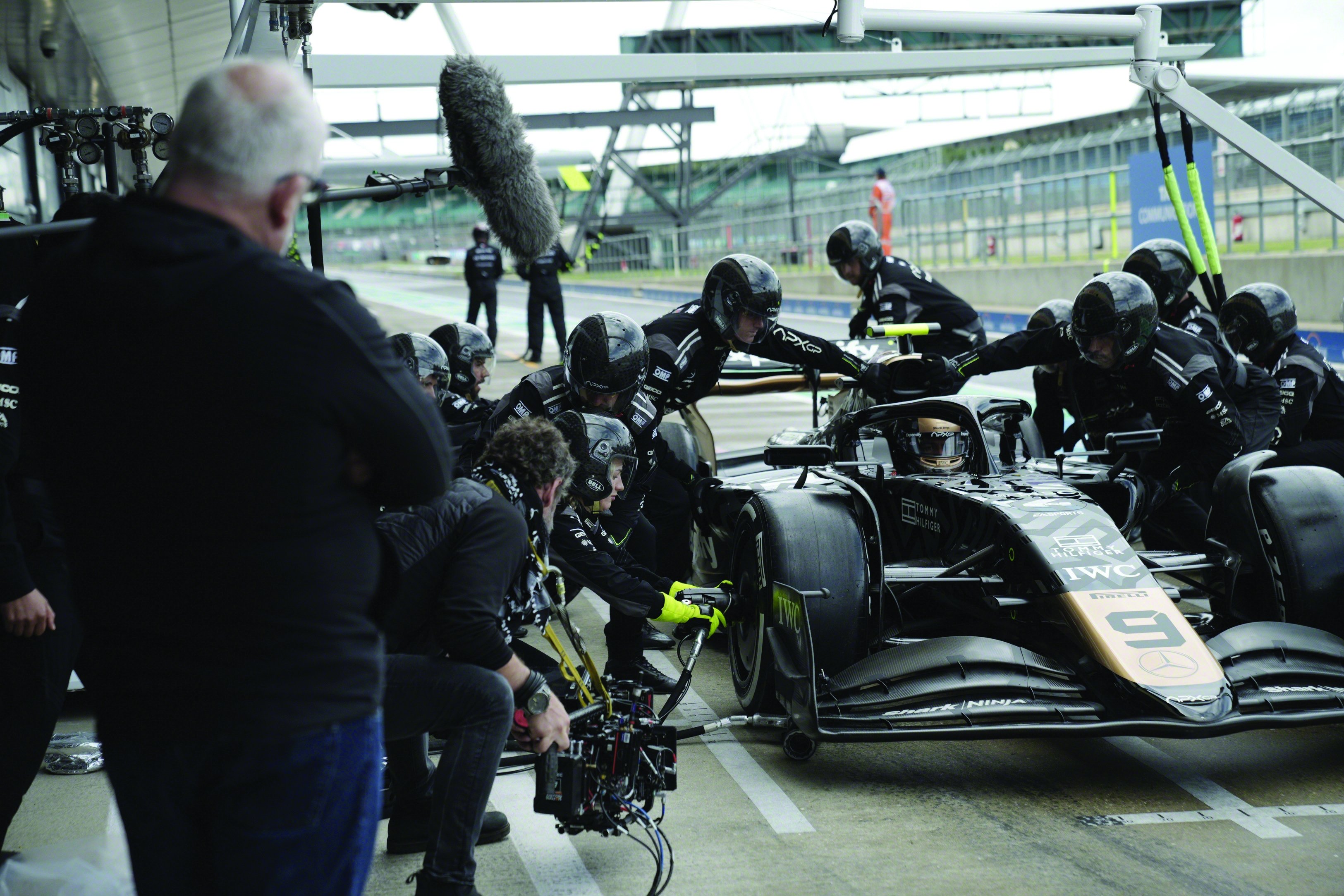

The production’s race cars were actually the heavier and less powerful models intended for the second-tier F2 league administered by the Féderation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), the governing body of world motorsport. The vehicles were modified by the Mercedes-AMG Petronas F1 Team to replicate the chassis of the longer Formula One vehicles. One electric car was used for pit-lane action and starts, and four vehicles with Mecachrome engines were deployed on the track. VFX on the cars largely involved digitally altering their skins to represent whichever team a scene required.

The filmmakers had 15 possible camera-mount positions spanning the cars’ front wing to the rear end, enabling them to cover the race action from every direction, but mounted a maximum of four cameras on a car for any given setup. Miranda and Ming worked with Panavision to develop remote-control pan heads with internal motors that would allow the Sony Carmen cameras to rotate 720 degrees. The cinematographer adds that the units also allowed the filmmakers to control focus, exposure, color temperature, roll and cut.

Ming explains, “The pan heads were remotely controlled from our mission-control area. Panavision built them specially for the Carmen cameras. The driving mechanism for the head used a Preston motor so that we could use the same motor driver [MDR] to drive focus as well as the pan.”

In each car, pans were executed via a pair of Preston Cinema Systems MDR-3 four-channel motor drivers plugged into RF Film’s onboard IP networks, which also connected the four cameras and wireless mesh radio. Separate 4K transmitters from Wireless Wizards and Hornets Tech sent a QHD signal for monitoring. Chrosziel motors drove focus. Ming details, “We designed the system using the Prestons because we knew RF Films could control them over an IP network, which was key while using a mesh network to cover the track wirelessly. So, we designed the heads with Panavision to use Preston motors to drive the pans. Also, with Preston motors, when you don’t send an input, voltage is sent to the motors to lock them in place. Some systems allow you to move the lenses by hand and will snap back to position only when you send a signal to it, which is bad in high g-force environments. So, with one MDR-3 motor drive, we had four channels, which could control two focus and two pans each.”

The manufacturer also built custom boards to power the entire system with Anton Bauer 26-volt batteries regulated to the Sony cameras’ required voltage. “We could only fit four recorders on each vehicle, [which is why] we were limited by space to four cameras per vehicle for each setup,” says Ming. “Due to bandwidth and video-transmission limitations, we kept a limit of 16 simultaneous cameras, total, between all the vehicles.”

Miranda notes, “Cameras and mounts were changed constantly; we could not put all the cameras out [on the cars]. It would have been too hard to drive, and we did not want to do unnecessary cleanup [by digitally painting out cameras from each other’s shots]. We used the cameras we needed for the shots we were trying to achieve.”

Two camera mounts occasionally faced the drivers on a riser less than 1" tall, which created just enough room for Pitt and Idris to see under them as they took a turn. All told, the filmmakers ended up with an estimated 5,000 hours of racing footage.

One car was essentially a dedicated camera vehicle, capturing POV shots and panning to cars beside it. Stunt drivers took the wheel for the more challenging bits of race work, donning the actors’ helmets.

Action-vehicle supervisor Graham Kelly and his team assembled the cars and helped secure the equipment inside. The longer bodies of the F1 vehicles created more space for gear in the floor trays (components located beneath the car, near the front axle), including the recorders and battery plates. “We had to make sure we could run our cables from the floor trays to any of the camera-mount positions,” notes Ming.

Then there was the matter of operating the small cameras remotely. Miranda recalls, “My concern was, ‘Can we control the cameras and whip-pans through all of the track? What system would work?’” The production turned to wireless-video specialist Greg “Noodles” Johnson of RF Film. “Noodles was able to get our [Carmen panners] networked around the whole track with video, focus and camera control,” Miranda continues. “So, if I couldn’t change an ND, I could change ISO on the fly. He worked closely with Dan Ming to help with all of this integration.”

“Lights Out”

Everything was put to the test when principal photography kicked off in July 2023 at the British Grand Prix on the Silverstone Circuit. To chronicle the ups and downs of the fictional Apex racing team’s season, the production piggybacked on the actual Formula One calendar, setting up at races in Hungary, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Mexico, Las Vegas and Abu Dhabi, where the main unit and actors were usually on hand.

The movie includes actual race footage supplied by Formula One and its teams from various trackside cameras, lipstick cameras buried in the track, and a cablecam; some of these placements were made at the filmmakers’ request. Ming notes, “Claudio tweaked camera settings for more compatibility with our [main production cameras], Sony Venice 2s, and Joe would have meetings with the broadcast team before each race to tweak certain angles if there was a specific shot we needed at a specific turn.”

F1 teams typically have two “camera pods” on their cars — housings for both cameras and transponders that can transmit data — but the 720p broadcast cameras they typically contain had to be replaced with custom units that would satisfy the production’s high-end cinema demands. The solution could not add extra weight to the vehicles.

In collaboration with Formula One, the FIA, and engineers at Apple, the filmmakers opted for iPhone technology; the tiny custom cameras, capable of shooting 4K raw, were placed on two competing cars during races. Ming explains, “We found that the iPhones’ In-Body Image Stabilization did not work well with the high-frequency vibrations and violent g-forces we were working with, so when Apple designed and built the custom wing cameras for the F1 cars, we had to go back to an older chipset that didn’t have that feature.”

For aerial work, the production favored helicopters over drones. “Joe and I watched some FPV drone footage of races and got so turned off by the slickness of it,” Miranda observes. “We kept it more cinematic and were able to do a lot with helicopters. For the Daytona section of the movie, Kevin LaRosa II served as pilot and Michael FitzMaurice was the operator; they had worked with us on Top Gun. Various pilots and operators handled other sequences.”

One of those helicopters provided a variety of footage for the movie’s opening sequence, which shows Sonny competing at the 24 Hours of Daytona race. The chopper was visible in one shot, so the production’s visual-effects team digitally altered it to resemble a TV-news chopper — although Miranda notes, with a laugh, that its presence so close to the track would be highly improbable at a real race.

Immersed in the Action

To take advantage of the large crowds for wide shots, the production shot on the racetracks with the actors and stunt drivers in brief windows when there were breaks in the action during real qualifying rounds. “It was a rush to see Brad really going out there with all the race fans watching,” says Miranda. “The ADs would give them Apex racing-team signs and rally the crowd with, ‘Hey, it’s Brad Pitt, put your hands up!’”

At the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix, after the three actual finalists left the winners’ podium, three cast members walked on and performed their own champagne-popping for the cameras in front of the cheering throng. “It would take us longer to get through all our setups, and eventually the crowd would thin out,” Miranda recalls. “We sometimes left our cameras in shots. I was operating a crane for a wide shot in which you’ll see another operator shooting our close-ups. We dressed them to look like press.”

Formula One gave the Apex team its own garage in the pit lane next to the official teams’ spaces, allowing the filmmakers to shoot scenes with their actors as real racing action unfolded around them. “We had to be light on our feet, and equipment had to be minimal,” Miranda says. They also had to be mindful not to interfere with the airwaves: “I had to work with F1 during races to make sure we weren’t jamming any of their cars with all of our electronics. That was super-critical.”

The need to be nimble at races led the filmmakers to use a DJI Ronin 4D with Sony G Master lenses, with the crew controlling iris and focus remotely. “That allowed us to be a little mobile unit running through the paddock,” Miranda explains. “I was stressing to people, ‘Let’s keep it small.’ I wanted something self-contained.”

A-camera operator Lucas Bielan handheld the Ronin 4D for a tracking shot at Daytona in which the napping Sonny is awakened by a knock on the door of his van. He steps out into the midnight air and walks down a path to his team’s car, where he testily replaces his teammate for the next leg of the endurance race.

For the race at the Silverstone track in England, production set up their cars behind the real drivers at the starting line and shot them as they all took off — except for Sonny, whose car mysteriously stalls. “I wanted a crane-type shot of the start of the race,” Miranda says. “The Ronin 4D has an extension system similar to the Venice Rialto extension system. The gimbal and head separate from the main system, allowing us to put the gimbal head at the end of a speedrail pole, making a very small crane. Ideally, I would have had a normal crane, but that was not an option; we had to clear everything in under a minute. I tried to have a driving crane, but that was not allowed, so we did it small and cheerful.”

Lens Arsenal

Most off-track scenes were shot in the U.K. with Sony’s Venice 2, equipped with Arri/Zeiss Master Prime lenses; Miranda sometimes operated A camera, while B camera was operated by Natasha Mullan. A third camera was occasionally needed. The filmmakers captured mostly in the Venice 2’s Super 35 mode at 5.8K 17:9 to satisfy both the traditional 2.39:1 aspect ratio for most theaters and home screens and 1.90:1 for digital Imax exhibition. For certain shots, including some helicopter footage, they shot at 8.6K 17:9 full frame in case the VFX team needed to do any replacement work.

For plate photography, Sigma FF Prime lenses were deployed. “We shot a lot of plates — usually background plates with crowds — since we couldn’t get all the angles of a scene live,” Ming says. “We’d shoot what we could live at every race, but we’d have to clean up some scenes after the races had moved out. We shot full frame to get maximum resolution.” The camera team shot in full-frame mode when using the 150mm Master Prime to achieve shallower depth of field. “I like the way it looks in full frame — it bleeds off the edges and gives you a bit of a different look,” the cinematographer says.

Zoom lenses were employed to simplify reframing while shooting races. On the ground, Fujinon Premier PL 18-85mm and 24-180mm zooms were used on cranes, the U-crane mobile arm and sometimes on the dolly. When the filmmakers wanted to reach as far as possible on the dolly, they called on the Premier 75-400mm.

In the helicopter, they selected from among the Fujinon Premista Lightweight 19-45mm, Premista 28-100mm and 80-250mm zooms for their full-frame compatibility.

The Rialto extension at 8.6K 3:2 full frame with the 10mm Voigtländer was deployed for a particularly significant driving shot. In an earlier scene, Sonny explains that he drives for that rare moment of grace when it feels like he’s flying, and he achieves that sensation during the season’s final race. The filmmakers convey this heightened moment for the viewer by adopting Sonny’s POV as he speeds down the track. “I couldn’t put a roll rig on the camera,” Miranda says, “so we shot at a higher resolution. A roll rig would be a device we could use to control the ‘rolling down the track’ shots remotely, but the rigs that were available were too big and clunky. Instead, we overshot the desired framing to allow for post roll. Since we were shooting 8.6K, we had plenty of resolution to do that. We shot wide and then, in post, we got the frame we wanted within the original shot and created that ‘rolling’ effect. We ran some tests on that and were happy it worked.”

Miranda composed for a 2.39:1 frame, aware that F1 would be exhibited in digital Imax on hundreds of screens. “With Imax [1.90:1], you still have a sense of horizontal framing, and you’re getting this extra immersion. We’re not hitting the Imax film 1.43:1 ratio, although Joe thought a lot about it — on Top Gun: Maverick, we opened up to 1.43:1 in the aerial sequences — but this movie has so much racing that he found it hard to go in and out of different formats so often.” (In the Imax version, after some introductory beach imagery and a cut to the Daytona race, the frame opens up to 1.90:1, where it remains.)

Available Light

Miranda had to work with available light at the races. For nighttime events, the tracks are commonly bathed in LED floodlights from tall towers, and the cars have rear lights and LED panels. Miranda is particularly fond of the look of the night race on the Las Vegas Strip Circuit. “Those lights are not stadium height — they’re put up just for the race, 20 feet in the air,” he says. “We got a much more staccato, flickering light on Brad as his car passed under them, which makes the race feel super-fast. Dedicated stadium lights are a lot farther away and don’t give the same fast light change.”

Most races, he adds, start around 12 p.m., which he calls “DoP hell.” At the British Grand Prix, the production was blessed with overcast skies. “The Abu Dhabi Grand Prix is the most interesting one because it starts about an hour before sunset and goes into twilight and then night,” he reflects. “It has a great desert low light and dusk. We had to change exposures, so there was a lot of dialing and playing around with the cameras.”

When Kosinski screened F1 for actual Formula One drivers, “they loved it,” Miranda reports, “but they got a little mad — jokingly — when our drivers would pass them in the movie! They were complimentary about the way we shot the movie and how it felt real, not gimmicky. That’s a great testament to the job we did.”

Unit stills by Scott Garfield. Images courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures, Apple and Sony.

Tech Specs

- 2.39:1, 1.90:1

- Sony Venice 2, FX6, custom FX6 Prototype ("Carmen"); DJI Ronin 4D; custom units with iPhone technology

Arri/Zeiss Master Prime; Sigma FF Prime; Voigtländer; Zeiss Loxia; Sony G Master; Fujifilm/Fujinon Premier, Premista

A Pit Stop With Kosinski

AC caught up with F1 director Joseph Kosinski in Montreal, where he was promoting F1 at the Canadian Grand Prix.

American Cinematographer: It’s been reported that you were inspired to make this movie by the Netflix docuseries Formula 1: Drive to Survive.

Joseph Kosinski: I’ve always been interested in [the Formula One] world. I got a degree in mechanical engineering with a focus on product design, then went to architecture school. This world was well suited to my interest [especially in terms of how] it works and operates.

During the pandemic, I watched the first season of Drive to Survive, in which they focus on the last-place team and rookies no one had ever heard of. It sparked the idea that this would be an interesting

way to enter this world — from the point of view of a losing team, rather than a winning one.

This is your sixth feature with cinematographer Claudio Miranda in the last 15 years. What allows this partnership to endure?

In addition to being a good friend and great person, he’s an artist with an amazing eye, but also an incredible technician who loves creative problem solving. I’m always looking for a new challenge and a way to capture something that hasn’t quite been done before. Often that requires R&D, going back to Tron: Legacy with the lit suit, then Oblivion with front projection, and Top Gun: Maverick and trying to get those cameras in a cockpit, leading up to this one, which meant we’d have to go much smaller and lighter than any camera system we’ve used before to [convey the speed of] these cars.

What did you convey to Claudio in terms of how you wanted this movie to look?

[Formula One driver and producer] Lewis Hamilton told me he’d never seen a racing movie that really captured what it feels like to be in the car. So, I said to Claudio, “We’re going to build racecars. We’re

going to teach Brad and Damson how to drive these cars, and then we need to capture it in a way that doesn’t slow them down and allows them to really drive.”

[I added], “And we’re not going to have control of the lighting. It’s not going to be like Top Gun: Maverick, where we can wait for magic hour every day. It’s got to be immersive, so when we’re in the car, it has to be wide-angle and close, plus [we need to] capture that sense of speed. We’re going to be ‘run and gun,’ in that we’re shooting during real Grand Prix events. Instead of having three hours to shoot a scene, we might have three minutes, which means using the available light.

At the same time, I don’t want it to feel like a documentary. I still want strong compositions and proper coverage. So, we’re going to have to be smart about how we use that three-minute period to get everything we need to properly cut a scene.”

What were the most meaningful references for you?

Grand Prix is the touchstone — [that film was] shot at real events in a beautiful [Super Panavision 70] widescreen format with great compositions [by director of photography Lionel Lindon, ASC].

They had an early version of an onboard panning camera that had one move, triggered by the driver. Another reference is the Steve McQueen movie Le Mans [1971, shot by Robert B. Hauser, ASC and

René Guissart Jr.]. I looked at those films the most, because although they are 60 years old, you can still watch them and be amazed. They capture a snapshot of a time and place, and I wanted [our] film to do the same.

Claudio told us that in the interest of realism, you didn’t want to do bluescreen and volume stage shooting.

No, avoid at all costs! You can feel that when you see the film. It’s really in the performances, and how we embrace the energy of the shoot. The camera shakes around, the drivers hit bumps, and that’s fine. We wanted to preserve all that.

You and Claudio collaborated with Sony on the compact onboard cameras, which you called “Carmens.” Did those cameras present any challenges?

We did some testing, and the vibration was so high that we had to redesign the mounts with a different material to absorb the vibrations so that we could get a decent image. We also had issues with transmission signals, so we ended up putting antennas all around the track to make sure we were getting picture. If you can pan a camera but you can’t see the image, it’s pointless. You need to control the camera and have an image with as little delay as possible.

We also had fancy, expensive lenses, and if the car in front hit some sand it would just crush the glass instantly. We had issues with bugs and rain, because the cameras do not like getting wet. So, there was constant modifying and improving as we went along; we were even adding mounting locations for the cameras right up until the last two races.

— Mark Dillon