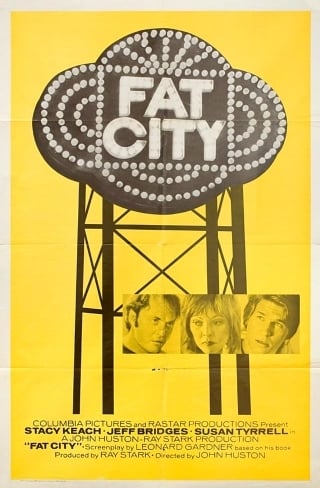

ShotDeck Drop: Fat City (1972)

Conrad Hall, ASC talks lighting by eye, destroying color and the human condition.

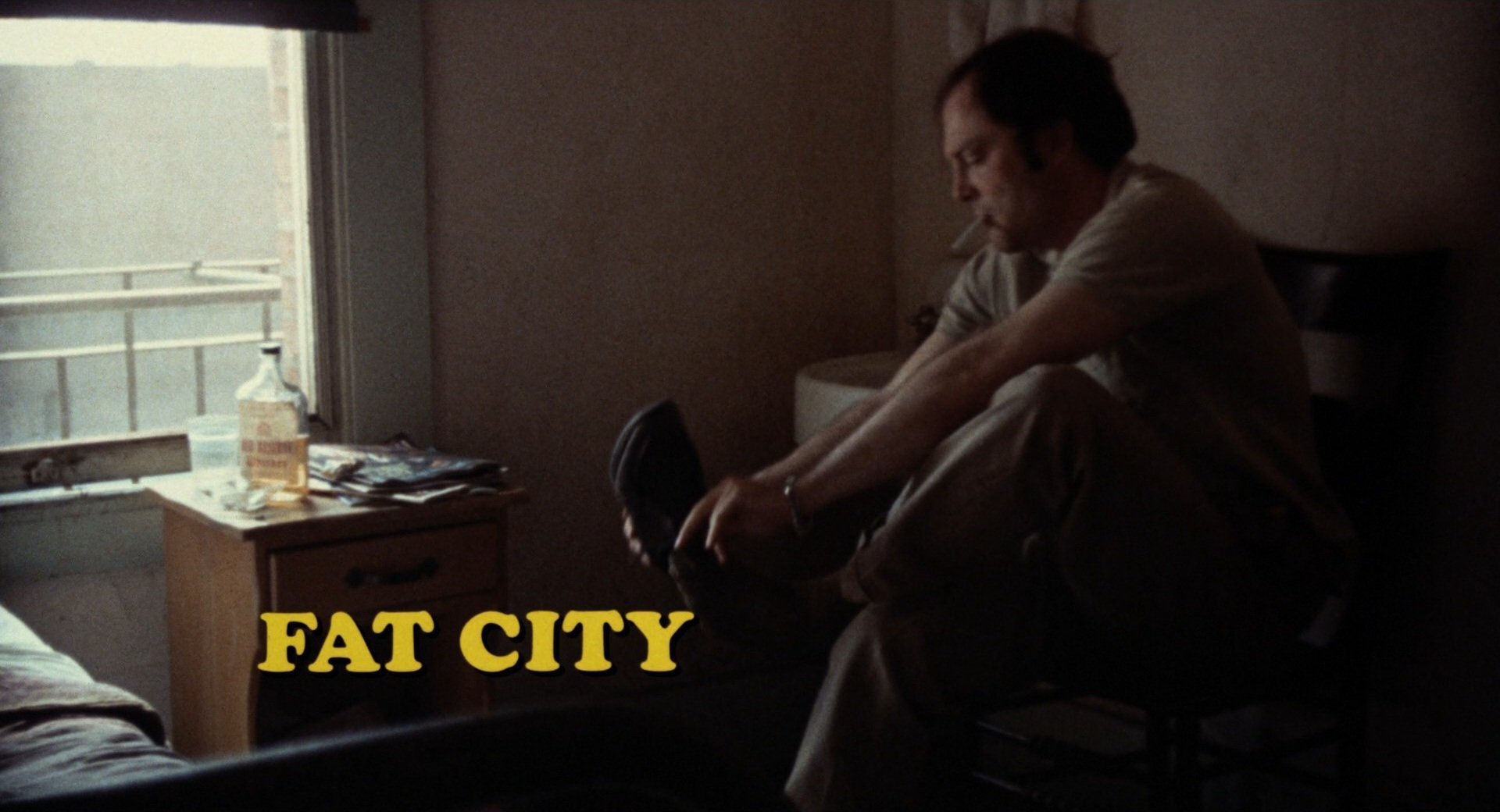

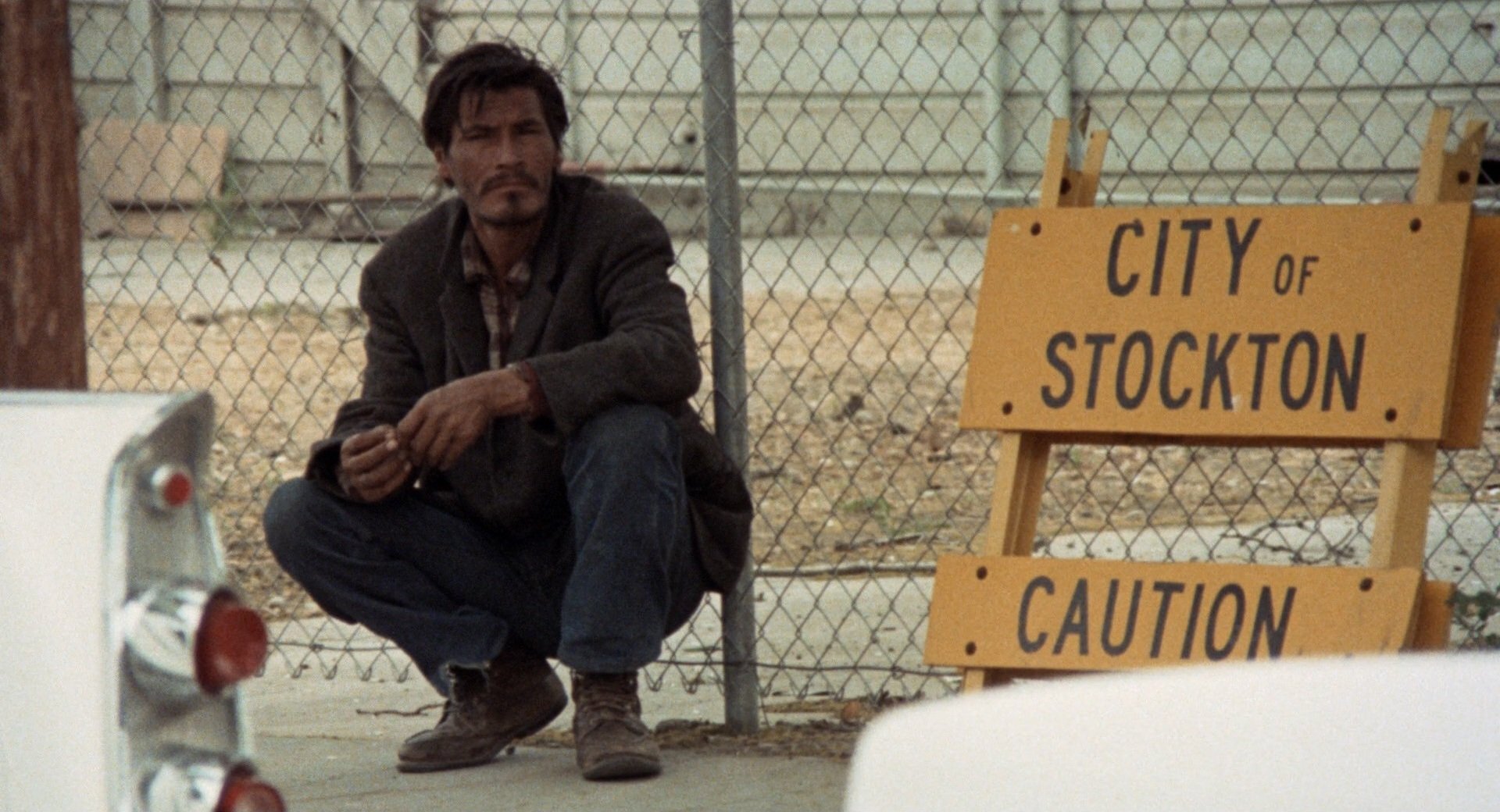

The visual research resource ShotDeck recently examined Fat City (1972), shot by Conrad Hall, ASC for legendary director John Huston (The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Wise Blood, Prizzi’s Honor). The film’s ironic title — a slang term for “the good life” — takes its name from the novel upon which it’s based, which in turn was taken from the town where it’s set, Stockton, in California’s central valley. Stacey Keach is Bill Tully, a 29-year-old drunk trying to resurrect his short but promising boxing career, and a fresh-faced Jeff Bridges plays Ernie Munger, a young, hopeful boxer whose star is on the rise. Hall’s gritty, naturalistic cinematography captures the melancholy of its setting, a world of poverty and despair, where any kind of good life feels like a far-off dream. “Movies are entertainment. They are a diversion from reality. But they can also make a lasting impression about the human condition,” Hall told AC on the occasion of his 1994 ASC Lifetime Achievement Award.

Hall was in the first wave of a new generation of cinematographers who broke into the industry during the 1950s and ’60s. He won his first Oscar in 1969 for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and earned other nominations for Morituri, The Professionals, In Cold Blood, The Day of the Locust, Tequila Sunrise, Searching for Bobby Fischer, and A Civil Action before winning again in 2000 for American Beauty (AC, June '00) and 2003 for his last film, Road to Perdition (AC, Aug '02). The latter two films, along with Bobby Fischer and Tequila Sunrise, also garnered Hall ASC Outstanding Achievement Awards for Cinematography. The cinematographer's other credits include such highly regarded pictures as Cool Hand Luke, Harper, Electra Glide in Blue, and Marathon Man.

The following commentary by Hall on Fat City — which he's called “the best” of his films — is excerpted from the book Masters of Light: Conversations with Contemporary Cinematographers by Dennis Schaefer and Larry Salvato (1984, University of California Press), and is available for purchase from The ASC Store.

The Opening Shot

“It's one of my favorite shots of all time. It's such perfect cinema. It's such a beautiful way of telling [Tully's] story at that moment in time. It's so precise. It was not overlit. It looked like you were using only the natural light.”

“There was a nine-light out on the window with only one bulb lit. I had two lit to begin with but that wasn't precise enough; it produced a sort of double shadow. So I killed one bulb. In that part of the scene when he finally walks into the foreground and goes through his jacket, I needed to light the wall behind that jacket so he and the jacket would stand out a little more. That's the only reason that light is on. I think I even had that light cut off at the beginning of the scene until we were over at the dresser and then when I panned over at that point, the light was on.”

“Actually it was more a camera movement problem than a lighting problem. I thought about using a crab dolly but I threw that idea out. I put a white card up in back of me in the hallway, on the wall opposite the doorway in the hall. I took a light and hit it into that white card so it would fill the room. But before I went with that shot, I just knew it wasn't right. I knew that pushing the film would allow me to see enough into the dark areas. I knew that the light coming through the window, which was six or eight stops overexposed, was enough to create like a fog filter. My craft was pretty precise at that moment, you see. Eventually I told my gaffer to kill the light behind me. He killed it.”

“I knew, at that moment, that I didn't need it... Maybe that's a symbolic way of showing what's happened to me with respect to lighting. I mean, I might start to overlight to begin with, but now I'm killing this source and killing that one because I'm getting better at it. I know what it'll do and what it won't do. I know how it'll do it, why it'll do it and, most of all, I know how to get what I want.”

Lighting With Natural Light

“That kind of lighting should be done very, very simply. You try to augment the realistic light. If you're in a bar and you have a couple of beer signs or a popcorn machine, you make those things actually do the lighting. You make them so that the film will recognize them the same way your eye recognizes them. And that they will have the same effect on the room that they actually do have on the room at night. It's not using 10K's and inky-dinks and things like that necessarily if there are other actual things available; it’s making the beer sign do the lighting for you.”

“You can put those lights on a rheostat and control the brightness up and down that way. Or you can take stronger bulbs than what are in the beer sign, and put them behind the sign. What you want to do is make the film see it the way your eye sees it.”

“It's the same way when you light a room with daylight; you take the basic daylight and you pump it up to actually do the lighting. I'd put some material over the windows and then pump lights through them so that it comes in soft.”

On Overexposure

“I was struggling with the primariness of color. I didn't like blue to be strong blue... I didn't like pure green or those vivid kinds of colors. I didn't see light that way and there's always atmosphere between color and me in the form of haze, smog, fog, dust. There's a muting of color that goes on in life. There was none of that in certain kinds of printing colors in film... I experimented with filters and fog filters. I used desaturation when we had imbibition printing. I tried all kinds of things: underdeveloping, overexposing and various lab techniques.”

“The overexposing was, I felt, a way of destroying the color. Without the use of filters, you could overexpose so radically that when you printed it you barely got back anything. But it was enough to be in color and it wasn't vivid anymore — because it had been destroyed so far. Not only would it destroy the color value but it would destroy the sharpness value. I felt film was too sharp; I didn't see life that sharp and I don't like it that sharp actually. So I always destroy sharpness. It may have to do with my own personal vision — my eyes, I mean. In other words, I know a tall man sees life differently than a short man; the angle is different, etc. There are a lot of psychological factors involved in how you see things and why you are specifically that way.”

“Overexposing is a technique, just like underexposing is a technique. It's another tool, that's all. But I knew it was going to be a valuable tool and I'd use it well some day. And I got a chance to do that on Fat City. When I started to shoot the film and employ this technique, the director [John Huston] liked it real well, the producer didn't like it so well and the studio hated it. So again there was not a lot of backing. But I persevered anyway and got it done. I can't say I would have done it better if I had had some back-up. I did it anyway and the only thing they could have done was fire me.”

The Look of Fat City

“Huston called the production designer and myself into his motel room to have a talk a day or so before [starting] the picture. And he asked me and the production designer, Dick Sylbert, what we thought the picture was about. I don't remember my answer but I remember Dick Sylbert's. He said the film was about life going down the drain before you had the chance to put the plug in. That's all I needed to know precisely what to do or to know precisely how I felt about it. I had known that but I hadn’t vocalized it. Sylbert vocalized it and Huston agreed with it and that was a very valuable experience in helping me to do my job.”

“Photographically speaking, I tried to make it real. I tried to make it the way it is. I tried to not make it look like a motion picture; I tried to make it look like a social study of down-and-out people rather than a slick way of looking at down-and-out people. I didn't want to beautify it in any way that would make it seem attractive. I made it abrasive; I tried to make the photography abrasive just as their lives were.”

“We tried not to be filmmakers at all; we just tried to follow life around.”

“I went out and shot some title material. They were tearing down part of the city where the bums lived to put a freeway through there; I think the only reason the city fathers did that was because they wanted to get rid of the bums but they didn't know how to do it. So they decided to put the freeway there and get rid of them, right? But instead of getting rid of them, the bums just move three or four blocks on either side of the freeway. You don't eliminate that element of despair in humanity by building a freeway and cutting out their habitat.”

“Anyhow, I got a camper/truck and put black curtains over the windows. I put a tripod at each window: the back window and the two side windows. I had a camera and a quick-change mount and I would just lift the camera and the head onto the appropriate tripod if I saw a piece of action. We cruised the streets looking for life running down the drain.”

“Then the first day we started shooting with actors, it all came back into perspective. You see, for three days I had been shooting by myself out of the back of this camper. And then we had a full crew and started shooting the actors. What a difference between reality and drama! I was fascinated with the difference in lighting between doing a movie and just shooting what was happening on the streets without any lighting at all. Shooting out of the camper, there was no lighting. And that allowed me to do that naturalistic lighting more precisely by actually seeing it. Seeing what happens with no lighting at all really allowed me to be better at it, to really see what it looks like and produce it.”

On Despair

“Maybe a few people went to see Fat City but nobody would have gone to see the film that I did for the first three days. It was about human despair. And I don't think we should be despairing of humans. I think we should try to make despair a palatable emotion to go to movies for. We should somehow show a way out. I don't mean to be cornball but there must be an escape.”

“To me, despair is a wonderful subject for motion pictures because it's such a common plight of man... And I just want to be able to go to a movie, pay five dollars, despair for two hours and not go out and shoot myself afterwards. I want to have a good despair; it's like people wanting to go have a good cry or a good laugh... That's why I take Fat City with me whenever I'm asked to speak. I want to find out how to make despair palatable because it's a worthy human condition.”

Founded by Lawrence Sher, ASC (cinematographer of Joker: Folie à Deux, The Hangover Trilogy, Garden State), ShotDeck is the world’s largest library of fully-searchable high-definition cinematic images. With over 1.6 Million shots and now an App for iPhone and iPad access, ShotDeck is an invaluable reference, planning, and collaboration tool for filmmakers, students and creatives of any kind.

Each week, ShotDeck makes hundreds of new, high-quality images available to users. AC will be regularly examining these projects with additional context and input from the cinematographers and other filmmakers involved in their creation.