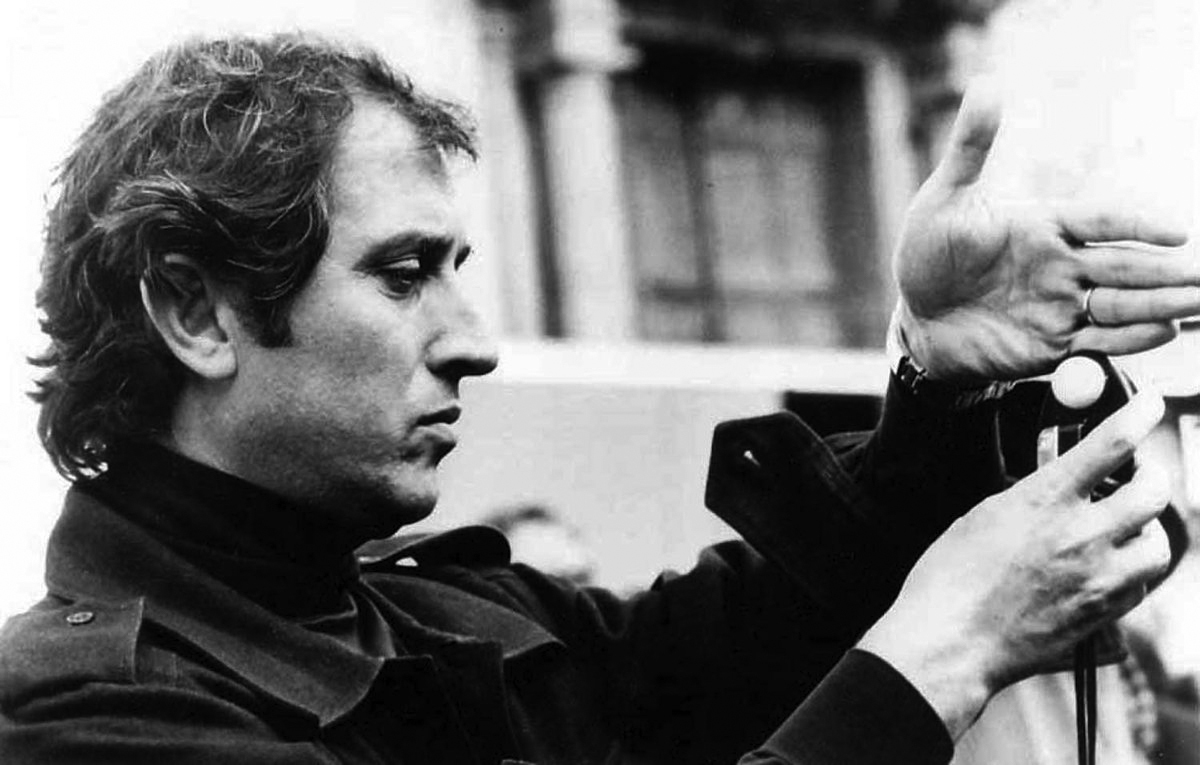

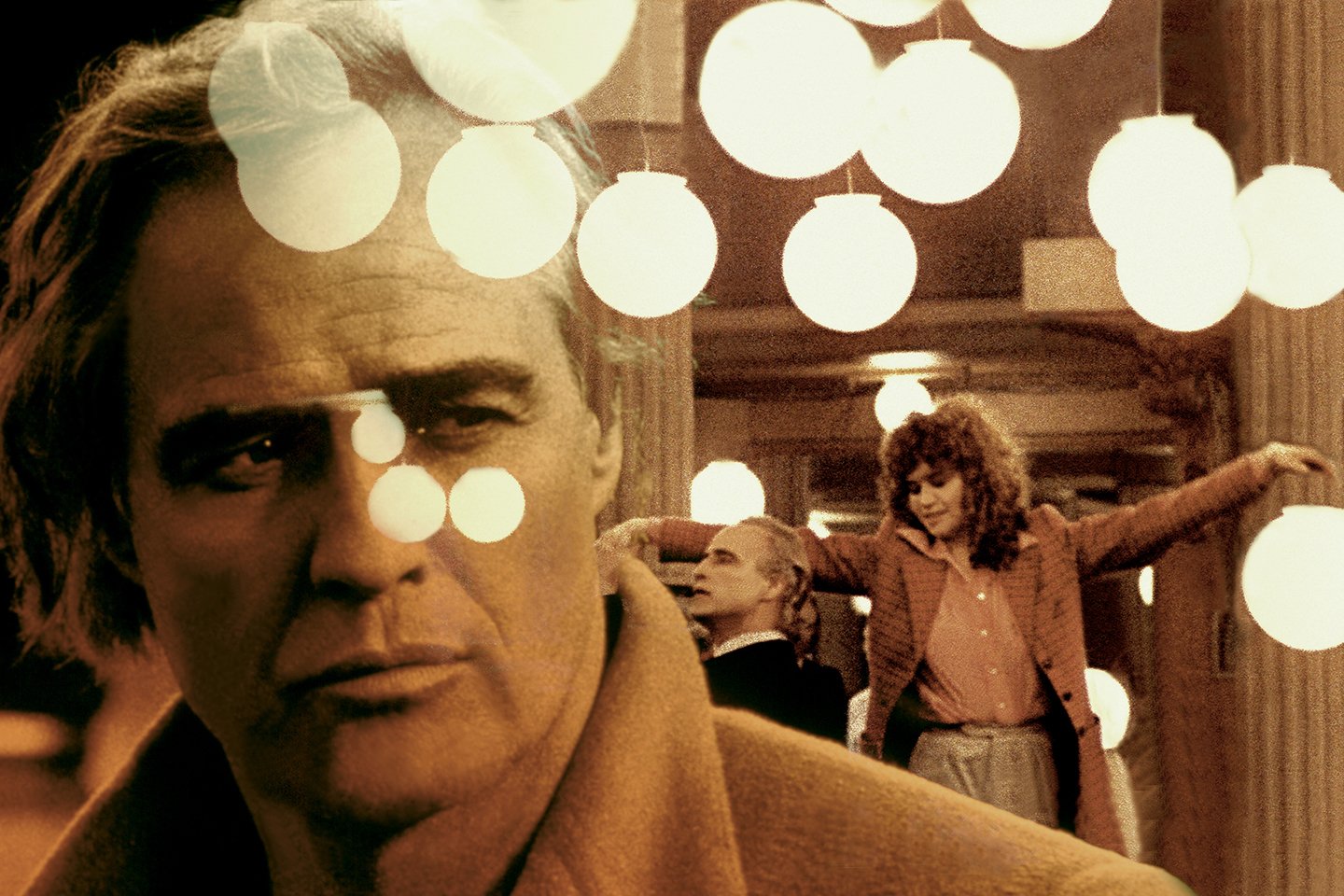

Photographing Last Tango in Paris

Discussing the cinematography in this exemplary 1972 film with Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC.

Living in Detroit, the only people I knew with a connection to the arts were proto-punk musicians like the MC5. For cinema, I had no role models. As a youth, I remember going to a tiny art house theater in a trashy Detroit mini-mall. When I walked out of the theater after seeing Last Tango in Paris, I felt like I was walking on air. I didn’t know that cinema could be so artistic, so sensual in its use of light and camera movement. It showed me what was possible, and inspired my decision to forsake the straight and narrow. Films like Last Tango gave me the courage to journey to N.Y. and L.A., knowing no one, and seek my own expression.

Steven Fierberg: Can you discuss the use of warm and cool light throughout the film to augment the story? In the bar where Maria encounters the old toothless lady, the use of sunlight versus dusk, in the Tango Palace where the light is cool, rather than warm as one might expect with those fixtures. Was this planned carefully in advance, or was more improvisational?

Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC: Since the first location scout in Paris, I had the idea to present Paris as “a city of light.” I was passionate about the contrast between the very warm artificial city light against the cold winter light. Brando’s character was visualized always with orange color, like a sun in its sunset time. Everything was very carefully planned.

There was great use of textured glass. Was this inspired by Bacon paintings, or how did you discuss with Bertolucci?

Yes, it was an inspiration from Francis Bacon’s painting.

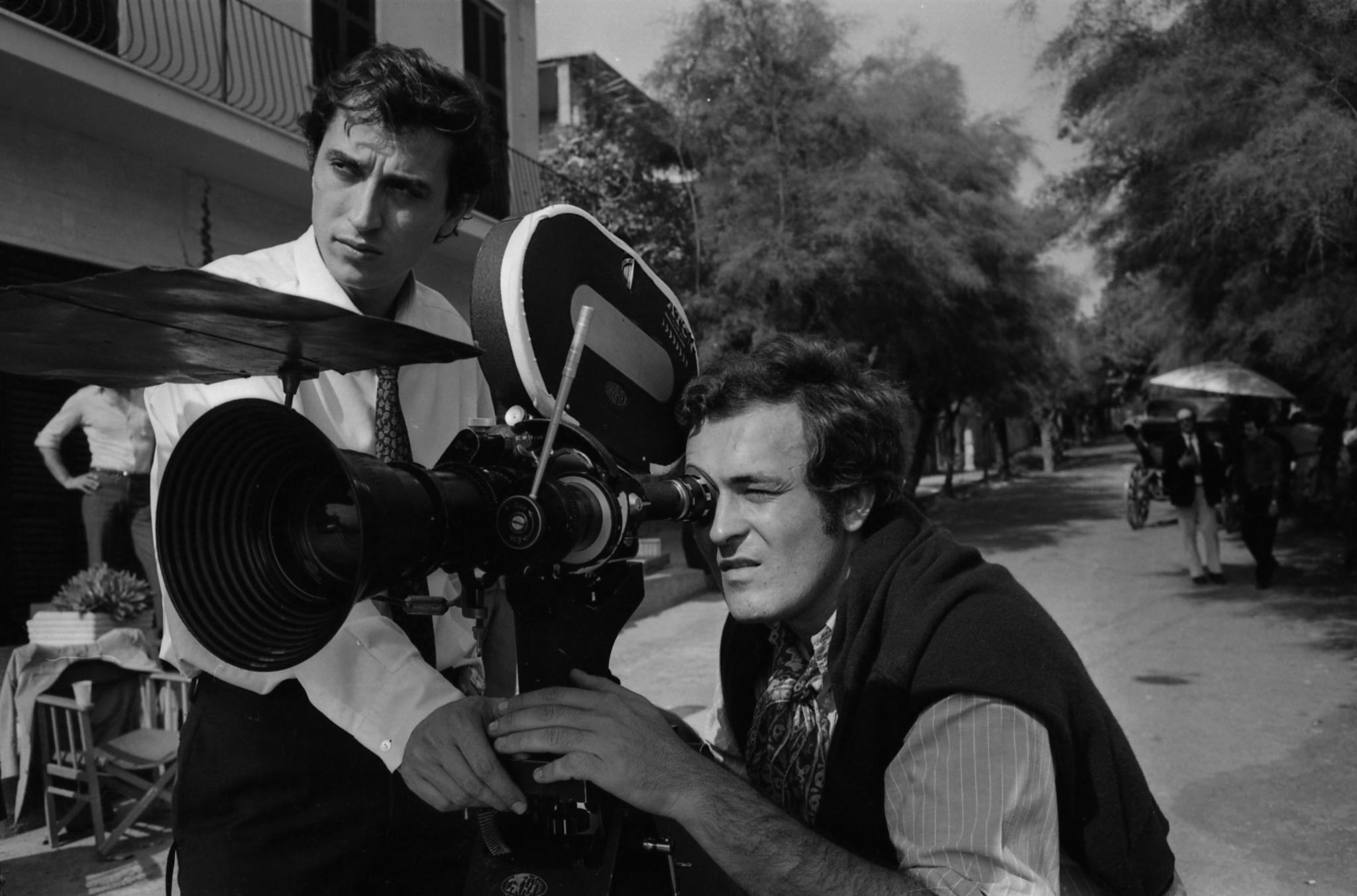

How much opportunity was there to find and walk through locations with the director before shooting?

I was filming a movie in Rome while Bernardo was preparing Last Tango in Paris. Every weekend I flew to Paris and we location scouted together. I was taking notes where I need to have some city light “on” and where I could use a warm sun’s beam, in sunset light, to represent Brando’s character. Paris bathed with the color orange was my main visual concept. Usually, Bernardo never told how he will shoot a sequence and I never told how I will light it. We know the main visual concept of the film and each other is doing his own visual journey in his mind.

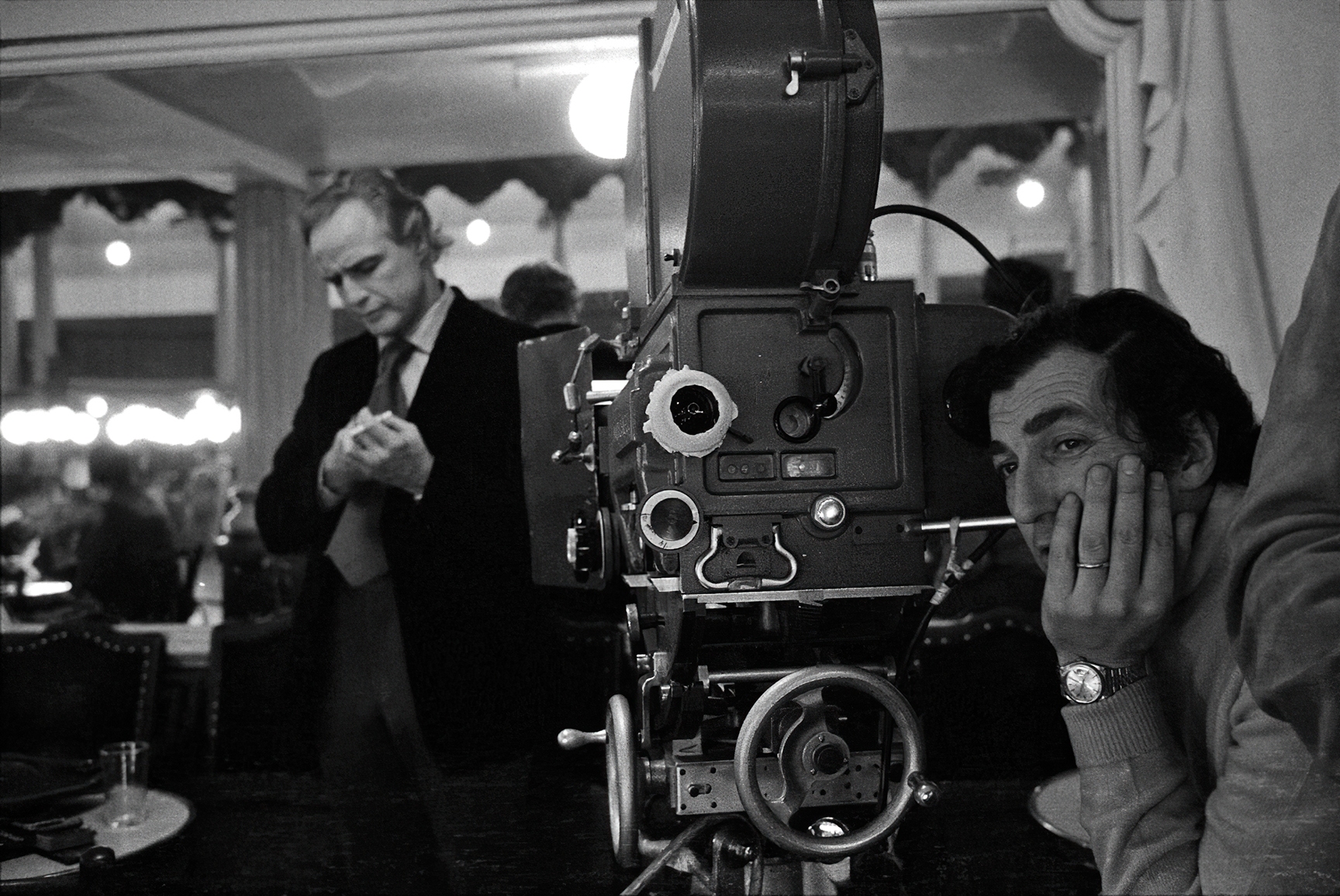

How did working with Bertolucci differ from other directors you have worked with? It seems to me that together you choreographed a “dance” of actors, camera and light. Can you illuminate this process, as I feel that it is a pinnacle in this film? One of the most shocking images for me as a student was seeing the camera tilt up with the elevator and pause on the round light fixture, celebrating its ‘light’ with a musical crescendo. I had never seen a film before where a director would care enough to do that.

It is Bernardo who usually “writes the story with the camera.” It is me who usually “writes the story with the light.” Bertolucci, looking through a viewfinder, created the mise en scene, with me next to him. After he explained the scene to the actors, Umetelli prepared the position of the camera with key grip while I prepared the light with the gaffer.

Was there rehearsal before principal photography started?

There wasn’t any rehearsal before principal cinematography.

Were rehearsals and staging or shooting done with the Gato Barbieri score played back?

Barbieri made the music after the shooting.

The shot where Maria enters and first reveals Brando in the apartment is my favorite shot in any film; the most perfect mixture of storytelling, camera, lighting and music to create the most beautiful imagery. Can you discuss how this came about?

The apartment was a real location, on the sixth floor. In the entire film, I never used light inside it. All lighting was prepared outside the window on a very little balcony. It was late in the afternoon and Umetelli told me that because of a very dark cloud the exterior was darker then the interior. I went in the camera and I asked Bernardo to film immediately, before it was complete night. Without video assist, it was the only way that I can see for myself the equilibrium between interior and exterior. By magic, during the filming, a sunset beam of light came through that dark cloud. It was very emotional for me, looking into the camera.

The use of the hall light versus the light coming in the window. What was the light coming through the window, how did you diffuse it or break it up? Were you using hard light through the windows, but with soft lenses, or did you diffuse the light?

There wasn’t any diffuse light coming into the apartment. [For softness] I used specifically for this film Bausch & Lomb lenses.

It seems to me that Brando is trying to “hide” from the light, and runs away from it, while Maria keeps chasing him and opening windows. Brando goes into complete silhouette in the middle of the scene. Then becomes “fractured” in the broken mirror. How elaborately did you collaborate with Bertolucci to rehearse this?

As I mentioned before, there wasn’t any rehearsal for this scene. The first take was the one. Marlon himself decided to hide from the light coming from the opening of the window. A genius!

I notice that Maria needed to hug the wall in order to stay in the shot as Brando moves into the second room.

We agreed since the beginning [of production] that Maria shouldn’t have any marks to respect for the camera. Bernardo explained to the actors the generic positions [that he wanted] but they were — particularly her — free to go in any place that they feel emotionally. The camera operator and dolly grip were to make little corrections according to their movements.

In the scene with Brando and Rosa’s ex-lover Marcel, when they sit together there is a beautiful warm light that is “hard’ but has a soft transition as Brando moves in and out of it. Throughout the film, you have hard light that is nonetheless soft enough to create softer shadows and a rich transition into darkness. How did you achieve this?

An artificial warm light was positioned outside the window for the two actors seated on the couch. A little table lamp was on the desk and a little light inside the bathroom.

How did you create the overhead light in the apartment?

There was not an overhead light into the apartment.

In the scene where Brando does a monologue about his father, the cow and the old man with the pipe, there is a moving shadow across his face that dramatizes the scene. It is supposed to be Maria; did you or Bertolucci rehearse and direct her, or is that you?

I personally moved between the light and Marlon, creating specific shadow on his face in order to feel the presence of Maria.

Late in the film is a scene where there is direct light with a rain pattern on the walls. Can you discuss how this conceived, and how it was done?

A very sharp light was positioned outside the window and a very little raindrops were put on the glass, creating the winter atmosphere on the scene.

In the scenes with Jean Pierre Leaud, for example, in the exterior where Maria enters a courtyard with curly hair and Leaud talks about “the camera is high,” the characters are frequently sunlit, in many directions. Was there a concept to keep the scenes with Brando overcast and grey and the scenes with Leaud with sunlight everywhere?

No. To show the change in Maria after having meet Brando, I keep the symbol of Marlon by putting in a beam of sunset light that follows Maria during the entire scene.

How did you create this sunlight? It is very specific and controlled. I know that later you were using aircraft lighting on dimmers, but what where you doing as this time, on all these street locations?

My only chance at that time, in Paris on location, were tungsten 10Ks.

I visited your set on Luna and it seemed you were often bouncing arcs into muslin, but this film has much more use of direct light.

Brando’s character of Paul character dictated the need, the use, of a beam of sunset light.

In the scene in the hotel lobby where Brando turns off the lights on Rosa’s mother, was this truly shot at magic hour? If so, was there only one take? Or was the exterior lit by you? My memory is at that time the film stock had difficulty mixing true tungsten color with the blue of daylight, but in this scene and the dance hall scene in Il Conformiste you achieve a perfection of color. Did you do this by modifying the tungsten inside — adding blue to tungsten lights — or how did you achieve this?

The principle idea was the different color temperature between natural and artificial light. In the hotel scene any interior was with white artificial light and the exterior, using artificial film negative, turned in blue color.

I have one more question, and compliment, that relates to il Conformiste. There is a scene in the children’s dance studio, where Trintagnant moves close to the window and becomes blue, as Dominque Sanda comes up behind him and undresses. To dramatize this crucial moment by having them become blue is brilliant and heartbreaking to me. Can you discuss how you conceived this idea?

The Roma atmosphere during Fascist time was visualize in monocromathic tones, without colors. The city of Paris symbolizes freedom, any exterior was visualize completely in blue color.

How did you achieve it, since I assume they walk into your light, rather than real twilight at the window?

The winter light in Paris is almost all the time close to twilight.

How in general you work to create a whole scene that seems to be done in twilight, like this scene, the giant dance hall sequence, the train station scene, as well as the twilight in Last Tango.With many shots and only a half hour or so of magic hour, how do you make this work?

The idea it is the most important thing. Filter or gelatin sometime can help to balance interior and exterior light, but the entire sequence is fundamental that will have the blue tonality.

Did you do special processing to achieve this? Were you using a film stock other than Kodak?

I used only Kodak in my all life. In this case it was 3200°K negative.

Fierberg’s work includes the feature films Secretary and Love & Other Drugs and the series Entourage and The Affair.

More detail on Storaro’s work in Last Tango can be found in his book The Art of Cinematography (L'Arte della Cinematografia).

In 2019, Last Tango was included in the ASC’s roster of 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century. Learn more about this list here.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.