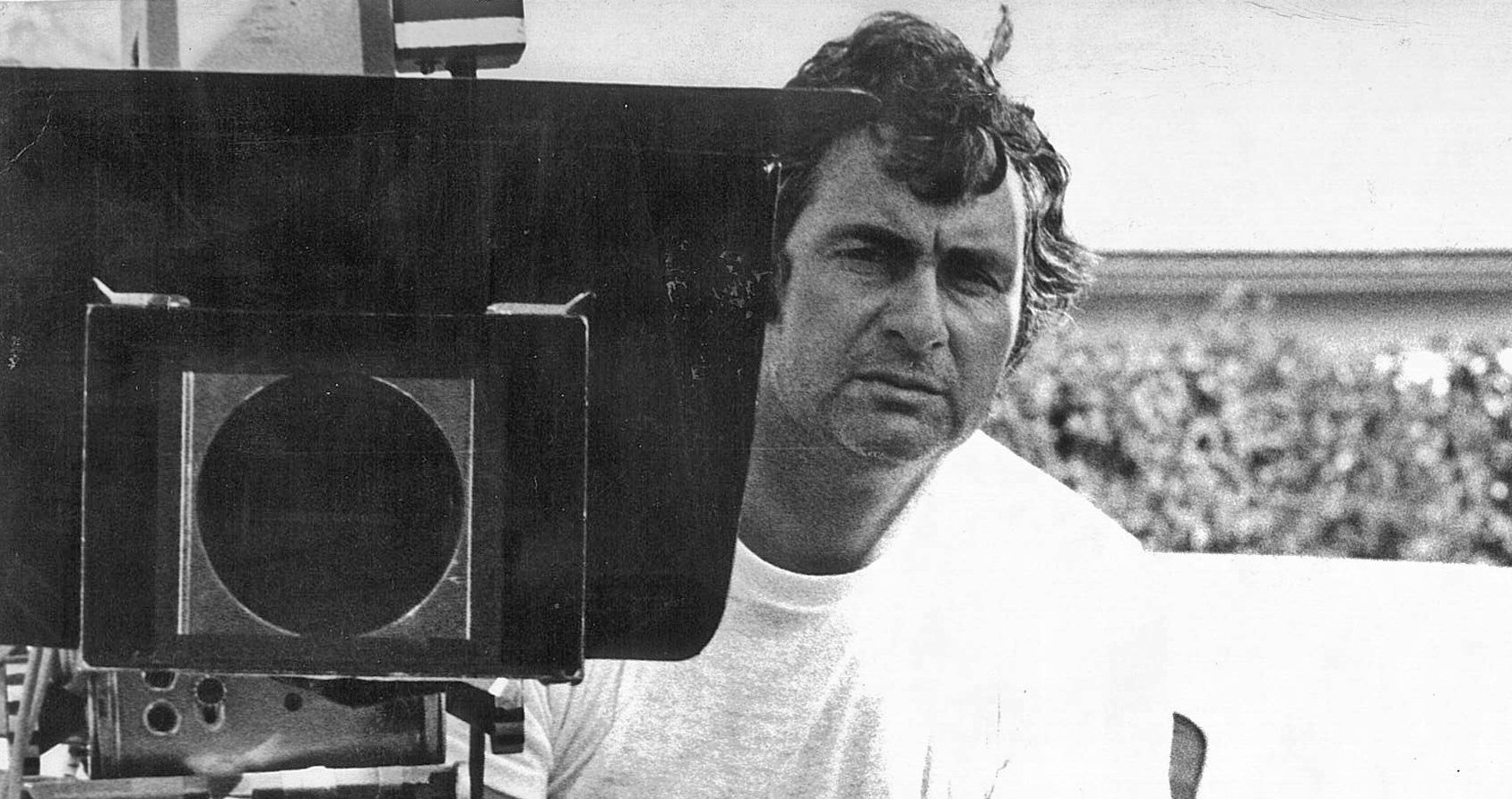

In Memoriam: Mario Tosi (1935-2021)

The cinematographer — best known for his work in the films MacArthur, Carrie, The Main Event and The Stunt Man — passed on November 11, 2021, at the age of 86.

The cinematographer — best known for his work in the films MacArthur, Carrie, The Main Event and The Stunt Man — passed on November 11, 2021, at the age of 86.

Born in Rome on May 11, 1935, Mario Tosi grew up during World War II and its aftermath. He studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts, earning opportunities to exhibit his work, collaborate with fellow artist Francesco Zonghi-Lotti, and win several awards. But he also soon realized that a painting career was far from lucrative.

A friend suggested that Tosi look into a career in motion pictures, as he could apply his painterly sense of light, composition and color to working as a cinematographer. He managed to learn the technical basics on his own through still photography, then gaining practical experience while serving on various productions in Italy, including as a camera assistant on the epic U.S. production of Ben-Hur (1959). In South Africa, he later photographed three black-and-white features between 1959 and 1962.

After relocating to Los Angeles in 1963, Tosi reached out to established cinematographers for advice on how to break into the business, with ASC members Hal Mohr and Arthur C. Miller offering their insight. Tosi soon learned that joining the camera guild was essential to success, and he focused on learning his craft to make that possible. Part of that education process was working for Fouad Said, the Egyptian producer, cinematographer and filmmaker best known for his Cinemobile system, a mobile movie studio that was popularized as Hollywood productions were increasingly shot on practical locations.

Tosi also learned by doing his own camera and lighting tests whenever possible and assisting other cinematographers on indie features. One of his collaborators during this time was future ASC great Vilmos Zsigmond, while shooting the disturbing drama Rat Fink (1965), which became a cult classic.

After shooting several biker movies and horror pictures (including The Glory Stompers, Frogs and Legends of Horror), Tosi was able to join IATSE Local 569 in 1970. Now able to work on union projects, and armed with experience in economical shooting on location, he soon built an enviable career in television, shooting commercials and working with creative directors on TV movies, including The Marcus-Nelson Murders (1973), directed by Joseph Sargent, A Summer Without Boys (1973), directed by Jeannot Szwarc, and Reflections of Murder (1974), directed by John Badham.

The cinematographer embraced the growing trend toward using soft-light techniques, often bouncing sources to achieve his desired naturalistic effect while using minimal fill. This was contrary to the established Hollywood hard-light approach of the day and more difficult to achieve with the sources available then.

In another break with Hollywood tradition, Tosi frequently used zoom lenses, but generally in the role of a variable prime. While the slower optics required him to work at higher stops than he would if using faster prime lenses, finding complete sets of properly matched primes was difficult at the time, and the color and contrast on a single zoom lens would remain consistent throughout its range, allowing him to better control his images. He felt the trade-off was worthwhile and compensated by simply adding a few more foot candles to his lighting and pushing one stop in the lab. This allowed him to maintain his naturalistic lighting approach and still take advantage of any available light he wished to maintain, as it need not be subdued by the need for excessive artificial sources simply to maintain a minimum stop.

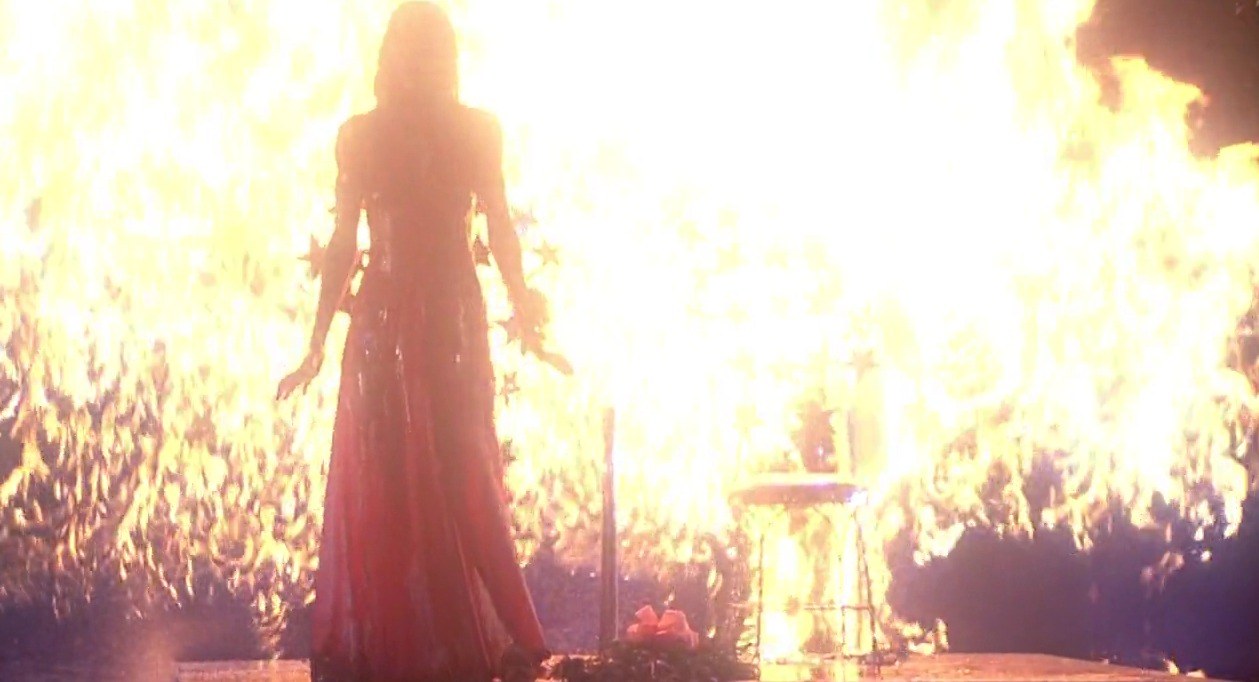

Tosi then gained notoriety with the stylish feature horror hit Carrie (1976), directed by Brian De Palma, which was an excellent showcase for the cinematographer’s artful talents.

The modestly budgeted went into production with Isidore Mankofsky, ASC behind the camera, but he and De Palma did not see eye-to-eye, leading to Tosi joining the show. The picture was shot over 50 days in the summer of 1976, primarily on locations in and around Los Angeles, with stage work done at Culver Studios.

While De Palma made great use of split-screen compositions created via optical printing in post — particularly in the horrifying prom sequence finale — he and Tosi also artfully used split-field diopters throughout the shoot to carry focus between different subjects in the same frame. (The director would later use this technique on numerous other pictures to great effect, including Blow Out, Body Double and The Untouchables.)

De Palma told Cinefantastique magazine in 1976: “I felt the [prom scene] destruction had to be shown in split-screen, because how many times could you cut from Carrie to things moving around? You can overdo that. It's a dead cinematic device. So I thought I'd do it in split-screen. I spent six weeks myself cutting it together. I had 150 set-ups, trying to get this thing together. I put it all together and it lasted five minutes and it was just too complicated. Also, you lost a lot of visceral punch from full-screen action. Then my editor [Paul Hirsch] and I proceeded to pull out of the split-screen and use it just when we precisely needed it.”

For Tosi, this visual approach was over-the-top. Commenting in a 40th-anniversary oral history on the production, the cinematographer said, “I guess [split-screen is] effective story-wise. I don’t think — to me, I think… it’s a little too gimmicky. But I guess it’s effective for the story, so I have nothing to say about that, because that’s all done in editing.”

However, the cinematographer added, “Today, after 40 years, after 40 movies and more that I did, experimenting with soft light and bounce lighting… I would have probably done it differently. But, 40 years ago, I would say that what came out [of the process] was brilliant.”

Tosi was also especially proud of the fact that Carrie co-stars Sissy Specek and Piper Laurie both earned Academy Award nominations for their outstanding performances — a rarity in genre films.

In 1977, Tosi’s camerawork in the memorable TV drama Sybil (1976), directed by Daniel Petrie, earned him an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Cinematography in Entertainment Programming for a Special. That same year, he was recommended for Society membership by Haskell Wexler, ASC and welcomed into the organization by ASC President Linwood Dunn on March 8, 1977.

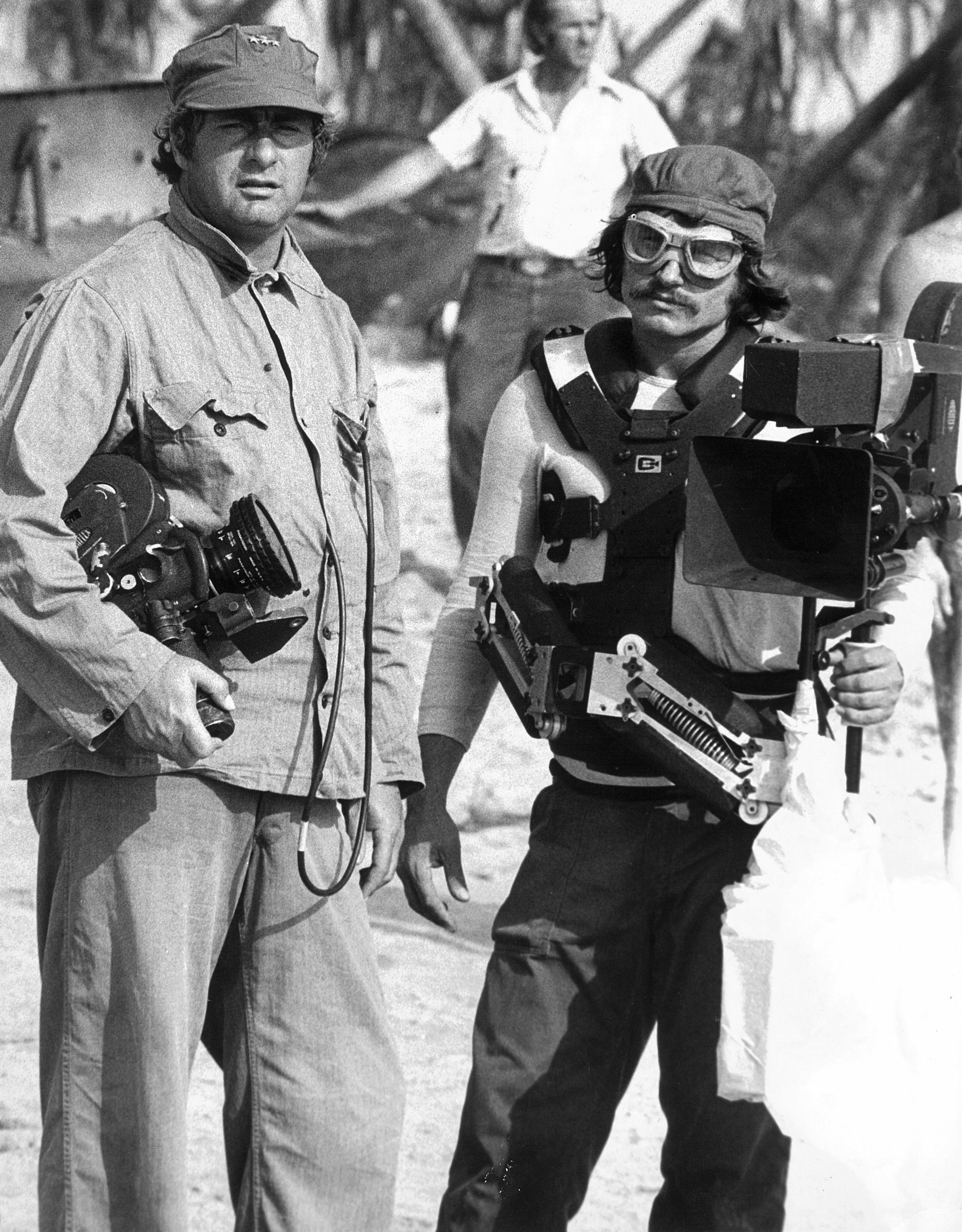

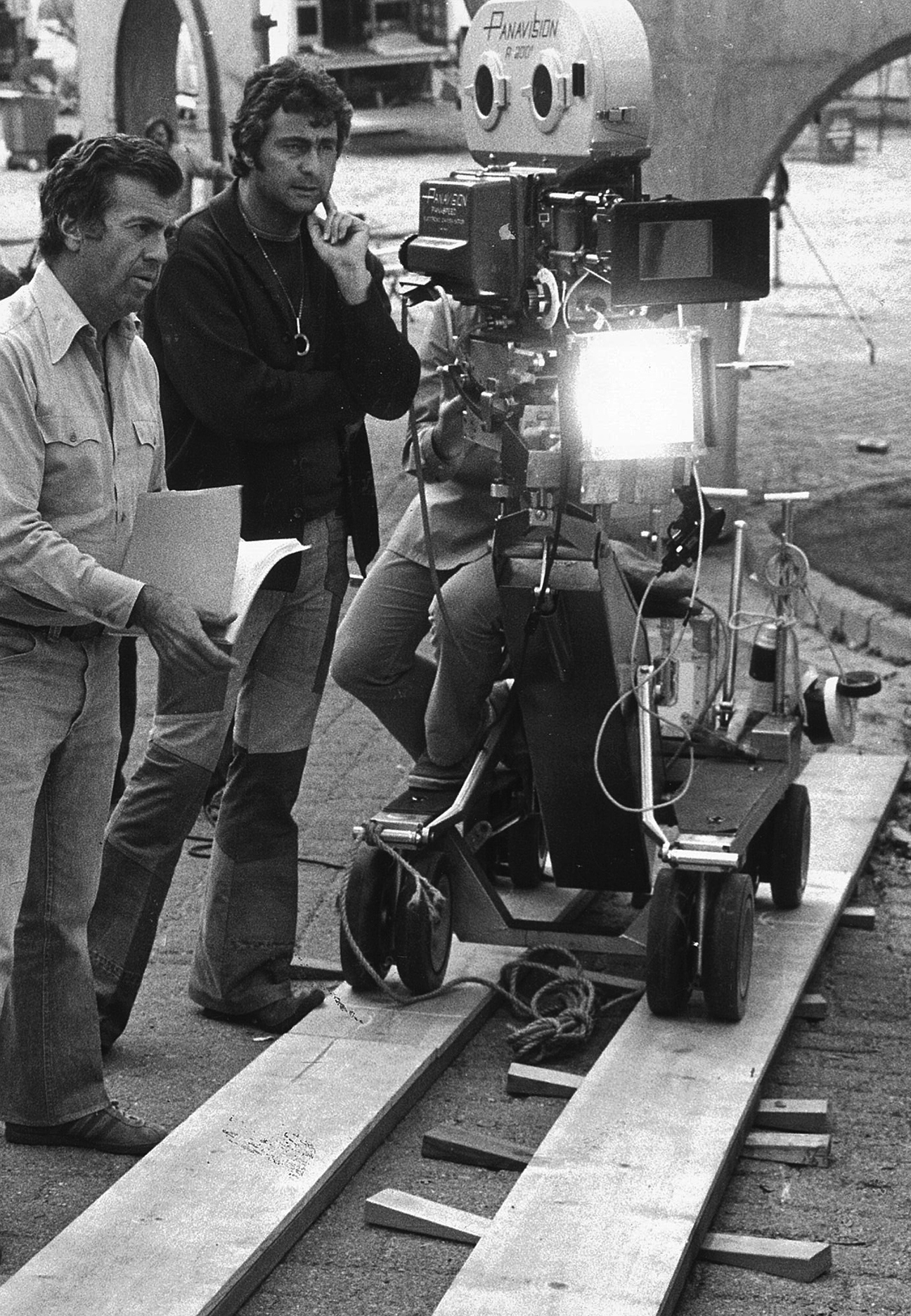

The cinematographer subsequently re-teamed with collaborator Joseph Sargent for their biggest project yet: the World War II drama MacArthur (1977), depicting the life of famed U.S. Army General Douglas MacArthur (played by Gregory Peck). “Joe Sargent and I agreed that we should make, first of all, a very ‘moving’ picture — one in which the camera would never stop, but would always be going someplace.,” Tosi explained in the July 1977 issue of American Cinematographer. “This would include dolly shots, hand-held shots, Steadicam shots and very smooth zoom shots. The reason for all this movement is that the story is about a man who is always talking with somebody — with the President, with a general, with a friend, with his wife. He was always talking, and we were afraid that it might become very static, so we made it move and, I think, very well.”

As the story primarily takes place during World War II, Universal Pictures believed stock footage could be used to depict combat scene that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive to film.

“Before shooting began, I was told that this movie was going to be crammed full of stock shots,” Tosi remembered. “Because of that, I was asked to make some tests to see how I could accommodate the stock shots and reach a visual compromise with them. Now, stock shots do not all have the same photographic character. Because they are shot in different locations and different years, they may all look totally different. I decided that I couldn’t worry about that. I said, ‘I am going to do this film in my own way and the way I feel it is going to look best. I don't care about stock or anything else.’ So I decided to give it a realistic, but classic look. I felt that everything should look like a painting and, at the same time, real. It should not have a documentary feel, but something different, more classic. This was the opinion of Joe Sargent, as well. He gave me the go-ahead. He said, ‘Make it as good-looking as you can make it.’”

After less than a week of shooting, Universal executives were praising Tosi’s camerawork: “They called it ‘great, fantastic, different.’ And so, the studio decided to put more money into the picture, which, fortunately, gave us the opportunity to shoot many more combat sequences than had been originally scheduled. As a result, in the final cut, the stock shots are very minimal — about 10 or 15. I am very happy about this, very relieved, because stock shots, as real as they can be, always create a jolt in the continuity of the photography.”

Shooting the comedy The Main Event (1979), directed by Howard Zieff, the cinematographer was tasked with making star Barbra Streisand look her best. In the 1984 interview book Masters of Light, by Dennis Schaefer and Larry Salvato, Tosi noted that Streisand and Zieff “wanted the film to look rather clean and stark. I would have liked it with a little more diffusion so it would look a bit softer. They objected to that because the picture was a comedy.”

Posted on the authoritative Streisand fan site barbra-archives.info: “During early tests and the first week of shooting, Tosi said Streisand ‘was trying to tell me where to put the lights and suggesting that we do things a certain way.’

“He explained that Streisand wanted to be photographed like she was by her favorite cameraman, Harry Stradling Sr. [ASC] on earlier films like Funny Girl and Hello, Dolly! ‘She wanted these big, enormous, old-fashioned scoop lights sitting on top of the lens. So we started with that but slowly I started bringing in my white cards and bouncing the light at an angle. She got used to it and, in fact, enjoyed it.’

“Tosi went on to tell authors Schaefer and Salvato that he was eventually able to ‘sneak in a few more elements of cinematography that I felt were necessary such as filters or a certain way of lighting. Gradually I was able to photograph her in different key [lighting]; she later told me she had never been photographed that way before.’

“‘With a lady, especially,’ Tosi stated, ‘you cannot use hard lights. The quality of the bounce light enhances beauty.” Tosi also confessed that he employed diffusion nets on the camera lens when he photographed women. “I started using nets a little bit with Barbra Streisand on The Main Event.’”

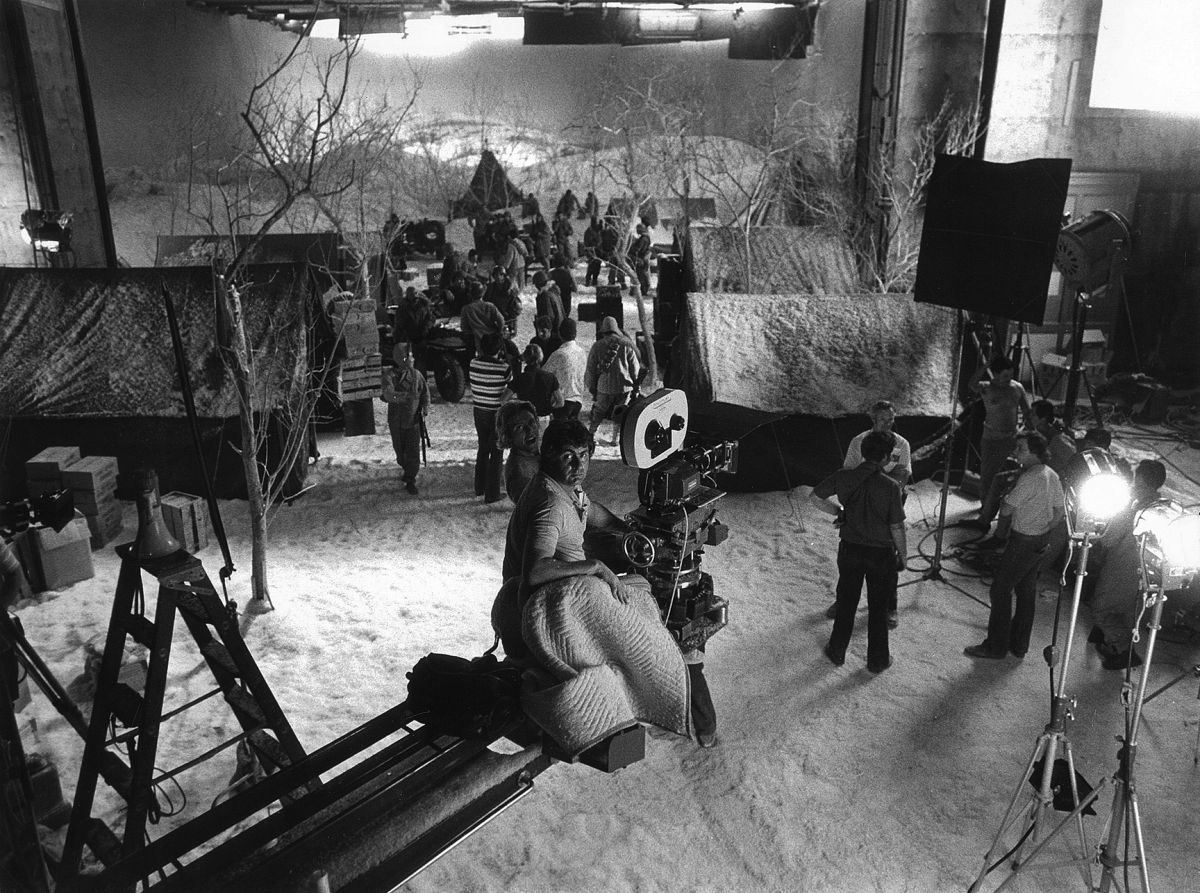

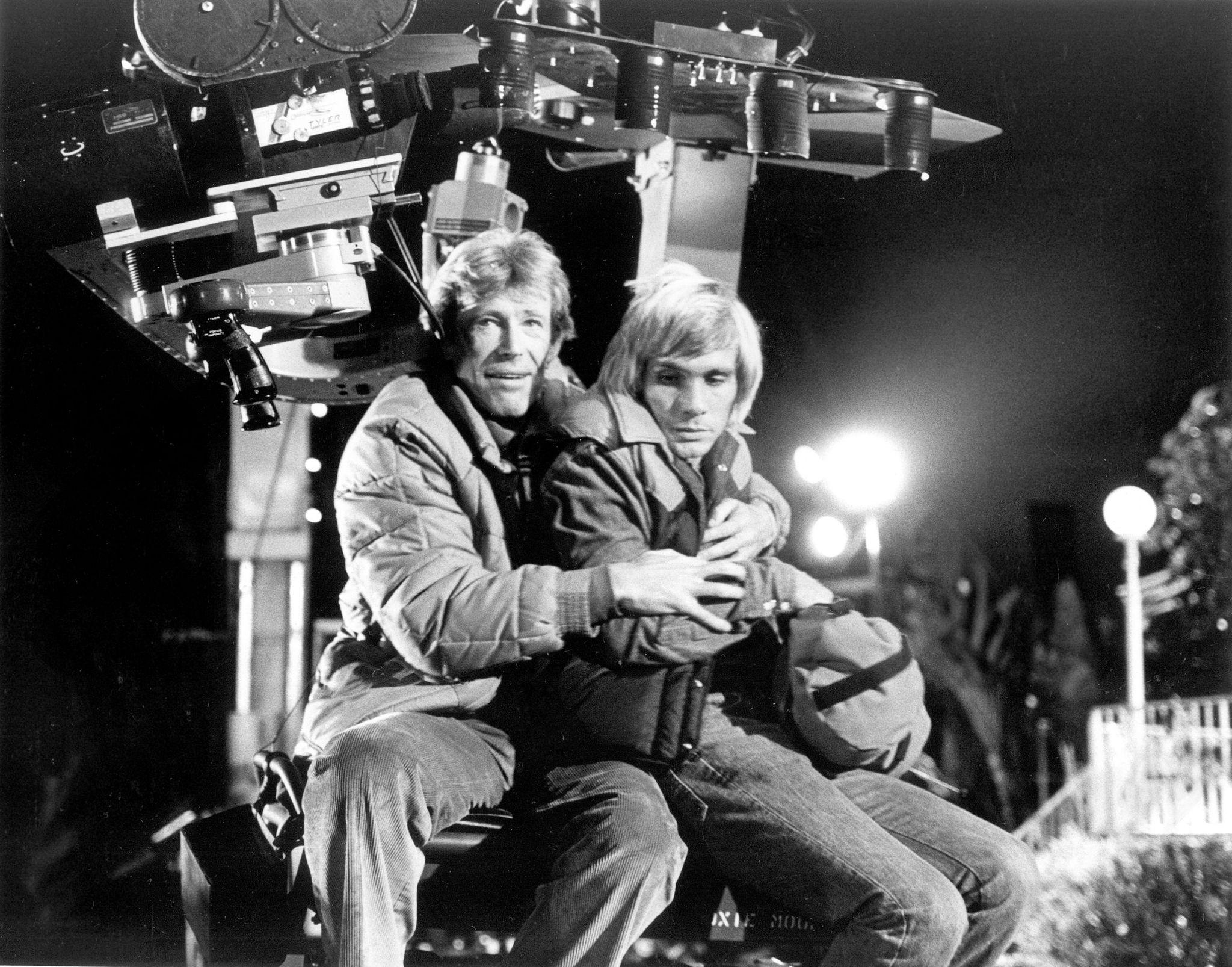

One of Tosi’s most challenging projects was The Stunt Man (1980), an action-packed Hollywood satire directed by Richard Rush that questioned the fine line between cinema and reality as a maniacal director (Peter O’Toole) toys with his new stunt performer (Steve Railsback) — a Vietnam vet on the lam who is also suffering from PTSD-induced paranoia.

In Masters of Light, the cinematographer noted that “the film was very difficult because of the stunts and the enormous amounts of different sequences, one after another. We also had a great number of problems due to the weather. The story itself is something between hard, human reality and fantasy, and I tried to bring this out visually in the film. I tried to make the fantasy evident but not too obvious.”

The director’s 2021 New York Times obituary noted, “Mr. Rush had definite ideas about the scripts he agreed to direct and how to shoot them. Mr. Railsback recalled that on The Stunt Man, the cinematographer, Mario Tosi, was taken aback by Mr. Rush’s hands-on style. “Early on Richard would say, ‘Put your camera here, do this and do this,’” [Railsback] said, “and Mario was getting upset because Richard was telling him where to put the camera and all this other stuff.”

But when the day’s footage (known as dailies) came back, Mr. Railsback said, Mr. Rush’s instincts proved to be spot-on. “Mario looked at the dailies,” he said, “and he walked over to Richard and said, ‘You just tell me where to put that camera.’”

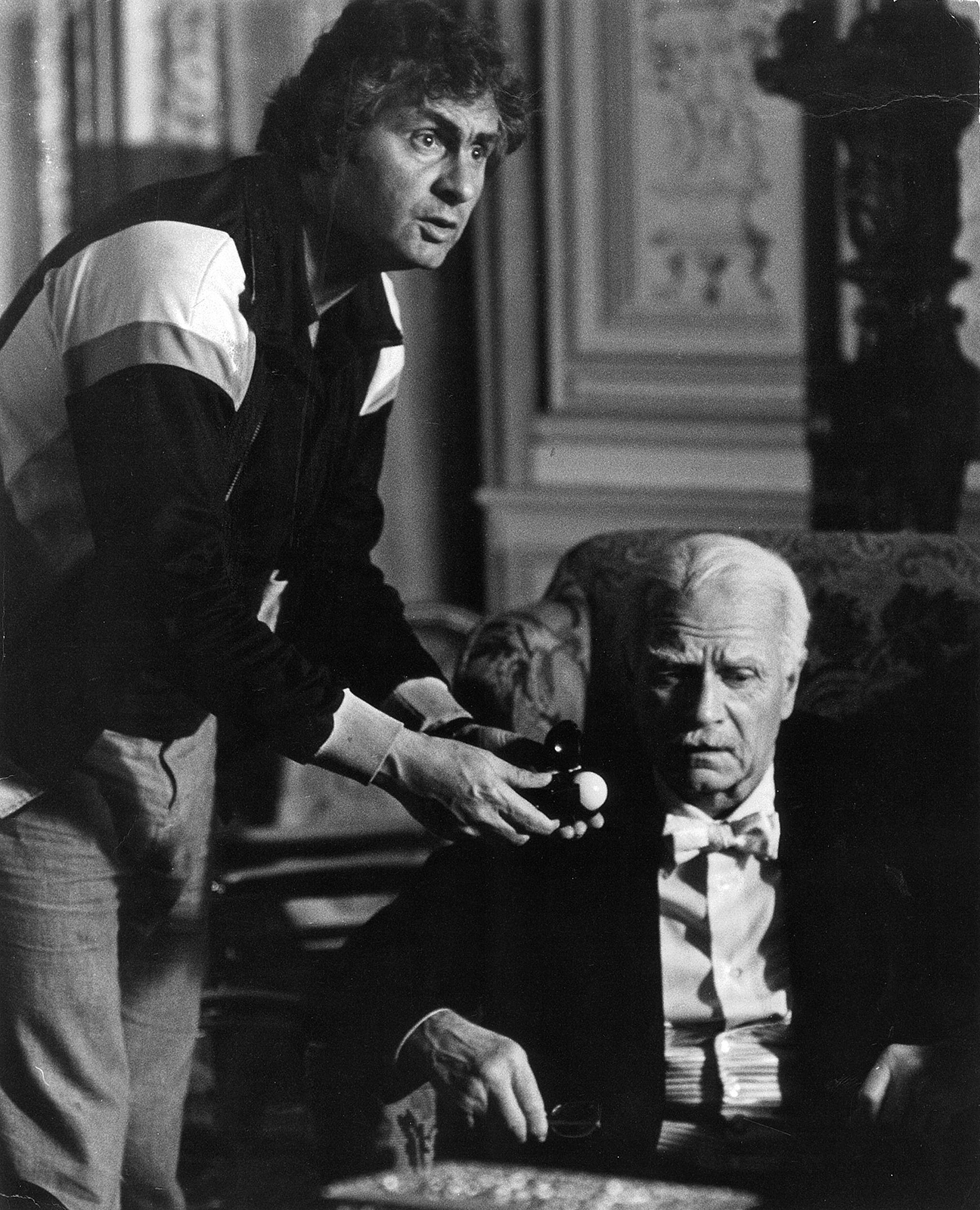

The cinematographer’s subsequent projects included the features Resurrection (1980), Coast to Coast (1980), Whose Life is it Anyway? (1981) and Six Pack (1982), and he was later the recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2009 Fort Lauderdale International Film Festival.

Tosi died while surrounded by his two children, Christopher and Valentina, and their mother. His obituary in the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel reported, “He was a very special man who enjoyed being a cinematographer, an artist, sailing and diving around the world, eating pasta and parmesan, and being a proud father. He shared his knowledge and success in his unique style which always had a profound effect on everyone around him. His love will not be forgotten.”

A service was held Fort Lauderdale on December 5, 2021.